Questions and Answers about COVID-19 Vaccines

On this page, you will find answers to some of the most common questions people are asking about COVID-19 disease and vaccines. Just click on the question of interest and the answer will appear below it.

Can't find what you're looking for?

You can also find information related to COVID-19 in these additional resources:

- Printable Q&A, "COVID-19 vaccines: What you should know" English | Spanish | Japanese

- “Look at Each Vaccine: COVID-19 Vaccine” webpage

- Animations: “How COVID-19 Viral Vector Vaccines Work” and “How mRNA Vaccines Work.”

Can I get a COVID-19 vaccine this year, and what should I know about the changes to COVID-19 recommendations?

COVID-19 vaccines for the 2025-2026 season were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on Aug. 27, 2025. These recommendations differed from the typical approach in two important ways. First, the FDA restricted use of COVID-19 vaccines to specific groups. Second, the FDA has historically been charged with licensing vaccines, not determining who should get them. Recommendations were the responsibility of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). We’ll get back to why this matters later in this update.

What COVID-19 vaccines are available and who can get them?

Four COVID-19 are available for different age groups:

- Comirnaty (Pfizer): This mRNA-based vaccine is approved for those 5 to 64 years of age with an underlying condition that increases their risk of severe COVID-19 and anyone 65 years and older.

- Spikevax (Moderna): This mRNA-based vaccine is approved for those 6 months through 64 years of age with an underlying condition that increases their risk of severe COVID-19 and anyone 65 years and older.

- Mnexspike (Moderna): This new Moderna option contains a lower dose of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. It is approved for use in those 12-64 years of age with an underlying condition that increases their risk of severe COVID-19 and anyone 65 years and older.

- Nuvaxovid (Novavax): This protein-based vaccine is approved for those 12-64 years of age with an underlying condition that increases their risk of severe COVID-19 and anyone 65 years and older.

What does the FDA licensure mean about who can get COVID-19 vaccines?

The considerations for getting a COVID-19 vaccine include three aspects, so we will address these for each group: Is the person eligible for the vaccine? Will the vaccine be covered by insurance? Where can the person get the vaccine?

Anyone 65 years and older: This group is eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine, and it should be covered by Medicare and private insurance. You will need to check if your healthcare provider has the vaccine in stock. If you typically get the vaccine at your local pharmacy, you should check about their policy this year. Some pharmacy chains are requiring prescriptions in certain states.

6 months of age to 64 years of age with a condition that increases risk for severe disease: People should talk to their healthcare providers to determine if they are in this group, and, therefore, eligible for the vaccine. We have included an image of a slide from the April 2025 ACIP meeting which outlines who is at high-risk based on scientific data for reference. If eligible based on these considerations, the vaccine should be covered, but you may want to check with your insurance provider since individual companies may vary in which groups they cover. You will also need to check whether your healthcare provider has the vaccine in stock. Depending on the age of the person, they may not be able to get the vaccine in a pharmacy. Likewise, some pharmacy chains are requiring prescriptions to give any COVID-19 vaccines in certain states.

Healthy children (6 months to 17 years of age): If your child has not previously had a COVID-19 vaccine, they could benefit from getting one. The FDA approval does not cover this group, but the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recommended the vaccine for all children 6 to 23 months of age as well as for those 2-18 years of age who have never been vaccinated against COVID-19 and whose household contacts are at high risk for severe COVID-19. Currently, the CDC’s immunization schedule allows for receipt of COVID-19 vaccine based on shared clinical decision-making (SCDM), so your healthy child should be able to get the COVID-19 vaccine. However, this could change when the CDC’s advisory committee, called ACIP, meets in mid-September. You will also need to check whether your insurance will cover the vaccine. While the insurance industry has generally stated that they will cover the vaccines, individual companies may not. If your child typically gets COVID-19 vaccine through the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, they can currently get the vaccine, but whether that will change when ACIP meets in Sept. remains to be determined. Finally, you will need to check whether your healthcare provider has the vaccine in stock and is willing to give it to your healthy child. Because of the FDA’s licensure that includes specific recommendations as to who can get the vaccine, a healthcare provider must be willing to give the vaccine “off-label.” While off-label use has historically been relatively common, it is unclear whether providers will be comfortable to do so in the current environment.

Healthy adults (18 years and older): This group is currently not eligible for COVID-19 vaccine based on the FDA’s limited approval. If you want the vaccine because, for example, you are a caregiver for someone who is at high risk or you are regularly around the public, you will need to check whether your insurance company will cover it or how much it will cost without coverage. And you will need to check whether your healthcare provider has the vaccine and is willing to give it “off-label.” You can also check directly with your local pharmacy to see if they are giving the vaccine and whether you need a prescription. If you need a prescription, you will need to see if your provider will write one.

Pregnant women: Pregnant women are no longer recommended to get the COVID-19 vaccine by either the FDA or the CDC, despite a significant amount of evidence* that they are at increased risk for severe disease if infected. This is why the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has diverged from the federal government’s recommendations and continues to recommend COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy.

A second concern around lack of vaccination against COVID-19 during pregnancy is that babies will be born without the benefit of boosted levels of maternal antibodies. Maternal antibodies are antibodies that babies get through the placenta during gestation. In the first few months of life, these antibodies afford protection against infection before babies begin to build their own immunity through infection or vaccination against pathogens. During 2024-2025, many children less than 6 months of age were hospitalized with severe Covid-19. Maternal immunization is the best way to protect these children.

If you are pregnant, you should talk with your obstetrician to see if they are offering the vaccine. It is anticipated that insurance companies will continue to cover this cost, given the data in support of this vaccination, but some companies may decide not to and if you are covered by Medicaid, it is unclear whether the cost will be covered. If your provider does not offer the vaccine, you may need a prescription to get the vaccine at your local pharmacy, so you should check in advance.

Source: Panagiotakopoulos L. 2025 Apr 15. Use of 2025-2026 COVID-19 Vaccines: Work Group Considerations. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

We will continue to update information on this page as more information becomes available.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

* “Epidemiology of COVID-19-associated hospitalizations, including in pregnant persons and infants,” "COVID-19 infection history as a risk factor for early pregnancy loss: results from the electronic health record-based Southeast Texas COVID and Pregnancy Cohort Study,” and ”SARS-CoV-2 infection elucidates features of pregnancy-specific immunity

What is shared clinical decision making (SCDM)?

Children are currently recommended to get the COVID-19 vaccine based on a type of recommendation known as “shared clinical decision making,” or SCDM. While some have associated SCDM with improvements to informed consent for COVID-19 vaccines in children, two considerations are important:

- SCDM and informed consent are two different concepts. Informed consent is supposed to occur before any medical procedure, including receipt of a vaccine. Families are given information called a “Vaccine Information Statement,” or VIS and they need to approve of receipt of the vaccine before it can be administered. SCDM, on the other hand, is a type of recommendation reserved for vaccines that may offer a benefit to certain individuals but may not be of benefit at the populational level. Some may feel that for COVID-19 vaccines, SCDM sounds like a reasonable choice, but in clinical practice SCDM typically results in fewer vaccines being administered, and COVID-19 continues to cause millions of infections, hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations, and tens of thousands of deaths each year. Although the disease is less severe for children, previously healthy children continue to be hospitalized and die from this virus.

- While any child can experience severe COVID-19 disease or lingering symptoms (i.e., long COVID), two groups of children are at particular risk. First, children with underlying conditions that increase their risk for severe disease should be considered for booster doses, similar to the recommendations for high-risk adults. Second, each year 3 million to 4 million babies are born in the U.S. These babies have not been exposed to the virus that causes COVID-19, but because that virus continues to circulate year-round and because most other people have some immunity, they represent a large group of susceptible people for the virus to infect. These children should get a primary series of the vaccine.

We know these two groups of children are at increased risk based on ongoing surveillance data*. For example, after the elderly, the youngest children (less than 4 years of age) are the second most hospitalized group. Second, in the 2023-2024 season, more than 150 children died from COVID-19. While those numbers are small compared with the thousands of adults and tens of thousands of elderly (65 years and older), as a society, we should not discount the effects of those losses on more than 150 families who will never see their children go to school or grow up and have families of their own.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

* “COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations — COVID-NET, April 2025 Update,” ”Use of 2025–2026 COVID-19 Vaccines: Work Group Considerations,” and “RFK Jr.’s War on Children”

Was Novavax approved under a regular license?

Yes. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently fully licensed the protein-based Novavax vaccine after delaying the approval, which was originally expected in early April. Importantly, when the FDA licensed the vaccine, they approved it for individuals 65 years and older and for individuals 12 to 64 years of age considered to be high-risk for COVID-19 because of one or more underlying conditions. This was a change from the previous approval under emergency use authorization (EUA), which allowed anyone 12 years of age and older to use the vaccine regardless of their health status.

The FDA is requiring additional studies, so the specifics of licensure may change over time.

Posted: May 21, 2025; reviewed June 24, 2025

Do DNA fragments in COVID-19 mRNA vaccines cause harm?

The short answer to this question is no, but let’s look a bit more closely.

The quantity

It is important to realize that mRNA vaccines undergo several steps during production, including multiple purification steps. This means that the amount of DNA fragments remaining in a dose of vaccine is extremely small. In fact, the leftover amount is so small that it can only be measured in nanograms, which are 1 billionth (with a “b”) of a gram or 1/1,000,000,000 of a gram. Think of it like one snowflake among 1,000,000,000 — an inconsequential quantity that would escape our notice unless we were looking for it.

The biology

With this said, some people might still be concerned that any DNA fragments are in the vaccine at all. First, it is important to realize that we are exposed to DNA fragments all the time. Anytime we eat plants or animals, we consume DNA, so our bodies need to protect against damage from foreign DNA. And while it is true that when we consume these fragments, they do not necessarily enter our bloodstream, like those in an injection will, we can still be reassured that our cells are designed to protect our DNA. Here are three relevant examples of how cells protect our DNA:

- Cytoplasm – As the vaccine is processed, DNA fragments may find their way to the cytoplasm of a cell, but our cells contain enzymes and immune system mechanisms for detecting and destroying anything foreign, so even if the fragments end up in our cell, they are destroyed.

- Nucleus – In our cells, our own DNA is housed inside the nucleus. The nuclear membrane acts like a moat around a castle, such that only with the appropriate “clearances” can something enter the nucleus. In our cells, these clearances are controlled by “nuclear access signals,” which are not part of (or accessible to) the DNA fragments.

- DNA – Further, for DNA to be changed, certain enzymes must be present. One example is integrase. Without integrase, our own DNA will not “open” to allow another piece of DNA to be added to it. In the example of the DNA fragments in vaccines, integrase is not present, so change cannot occur.

Some have also suggested that because the mRNA vaccine is delivered in lipid particles, the aforementioned description is not accurate. However, this is also a misconception. While the lipid particles help deliver the mRNA into a cell, the vaccine components are taken into compartments called endosomes. Endosomes contain acids and enzymes that break down the lipids and most of the DNA fragments, so they are quickly destroyed.

Learn more about these safety mechanisms: video | animation.

To find out more about DNA and other vaccine ingredients, check the “Vaccine Ingredients” section of our website.

Last updated: February 18, 2025; reviewed June 24, 2025

Are the mRNA vaccines a type of gene therapy?

The short answer to this question is no. Check out the article in our April 2024 Parents PACK newsletter to find out why.

Last updated: April 24, 2024; reviewed June 24, 2025

If young children do not get severely ill from COVID-19, why should I consider giving this vaccine to my child who is younger than 5 years of age?

As parents weigh the relative risk and benefits of getting their youngest children vaccinated against COVID-19, some wonder about the need for their child to get a vaccine when the disease doesn’t seem too bad in most children. Most healthcare providers agree that the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks for our youngest family members:

- As of June 2025, more than 2,150 children 17 years of age or younger have died from COVID-19. While this is a small number compared with the more than 1.2 million deaths in the U.S., for those families, their world will never be the same.

- Millions of children have been infected with the virus that causes COVID-19. Some of those children were hospitalized with severe disease or developed a condition called multi-inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), which can damage organs and on rare occasions be deadly. Importantly, it appears that newer variants are less likely to cause MIS-C. Watch this video in which Dr. Offit discusses this trend.

- Like adults, some children who have had COVID-19, even mild cases, have experienced lingering symptoms, commonly referred to as “long COVID.” In younger children it may be difficult for them to express what they are feeling or experiencing, which can make this condition even more difficult to identify and address.

- Millions of vaccines have been administered safely to children at this point.

For a more detailed look at the considerations related to COVID-19 vaccination of children and a series of resources, check out the March 2023 issue of Parents PACK and this April 2023 article penned by Dr. Offit, the VEC’s director.

Watch this short video of Dr. Offit discussing why children should get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Last updated: June 24, 2025

What COVID-19 vaccines are currently available in the U.S.?

The U.S. has four approved COVID-19 vaccines; those described as “mRNA vaccines” are the most often used. Bivalent versions are no longer available. Find out more about each vaccine:

- Pfizer mRNA vaccine – This vaccine contains mRNA to protect against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The 2024-2025 vaccine included the spike protein from the Omicron KP.2 variant. The 2025-2026 vaccine will include the spike protein from the Omicron JN.1 variant.

Moderna mRNA vaccine – Moderna has two versions of mRNA vaccine approved as of June 2025:

A. Spikevax: This vaccine contains mRNA to protect against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. The 2024-2025 vaccine included the spike protein from the Omicron KP.2 variant. If this vaccine remains available for 2025-2026, it will include the spike protein from the Omicron JN.1 variant.B. Mnexspike: This vaccine contains a lesser quantity of mRNA than Spikevax. Instead of containing the mRNA for the whole spike protein, this vaccine only includes mRNA for two parts of the spike protein. The 2024-2025 version, licensed in May 2025, contains the spike protein for the Omicron JN.1 variant. We wrote about this vaccine in the May 2025 Parents PACK.

- Nuvaxovid protein-based vaccine – This vaccine only contains the spike protein from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The 2024-2025 vaccine contained the Omicron JN.1 variant. This vaccine is approved for those 65 years and older as well as individuals 12 to 64 years of age who have an underlying condition that increases their risk for severe disease.

A fourth vaccine, J&J/Janssen adenovirus-based vaccine, is no longer available. This vaccine contained a replication-defective adenovirus that had been altered to include the gene (DNA) of the spike protein for the original SARS-CoV-2 virus. Because of the availability of other vaccines and due to the rare but serious side effects associated with this vaccine (i.e., Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS)), this vaccine was removed from the U.S. vaccine supply in the spring of 2023 and the company discontinued marketing the vaccine globally in mid-2024.

Last updated: June 25, 2025

What is the Novavax vaccine and who can get it?

The Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, called Nuvaxovid, uses a “tried and true” approach to inducing immunity. Specifically, the vaccine delivers the spike protein and an adjuvant, which is something that increases immune responses to the protein. It is given as two doses, separated by three to eight weeks, to those 65 years and older and those 12 to 64 years of age who have at least one condition that increases their risk for severe COVID-19. This technology is the same as that used to make one of the influenza vaccines (FluBlok) and very similar to that used to make the hepatitis B and human papillomavirus vaccines.

To find out more about the Novavax vaccine, watch this video of VEC Director, Paul Offit, MD, who is on the FDA’s advisory committee and, therefore, reviewed the data presented in 2022 when this vaccine was first authorized for use.

Last updated: June 25, 2025

Who should get a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine?

The scientific evidence indicates that four groups of people are most likely to benefit from a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine:

- Adults 65 years of age and older – This group can get up to two doses COVID-19 vaccine each year, with the doses separated by at least four months.

- Moderately or severely immune compromised individuals – This group may also benefit from more than one booster dose each year; however, the benefits vary based on vaccination history and age, so it is important to talk to your healthcare provider about your or a family member’s specific needs.

- Pregnant women – Although current CDC recommendations do not include this group, the data show that pregnancy increases an individual’s risk for severe COVID-19, so a booster dose can protect them from hospitalization or complications. Similarly, the booster dose increases maternal antibodies that can protect the baby before they are old enough to be vaccinated.

- People with chronic conditions – Certain health conditions increase a person’s risk for severe disease and can, therefore, benefit from a booster dose. Check conditions that increase risk on the CDC’s website.

Because anyone can benefit from higher levels of circulating antibodies, a COVID-19 booster dose around periods of increased viral transmission can offer protection for about four to six months.

Watch this video to hear Dr. Paul Offit talk about who should get a COVID-19 booster dose.

Whether all of these individuals will be able to get COVID-19 vaccine during the 2025-2026 season is unclear. Please refer to the answer to “Can I get a COVID-19 vaccine this year, and what should I know about the changes to COVID-19 recommendations?” for more details.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

My teen is a student-athlete and already had COVID-19, so does he need the COVID-19 vaccine? We are worried about myocarditis.

While myocarditis is rare, it is also real; so, we can understand why some parents may be hesitant to get their teens vaccinated. But it is important when making these decisions to realize that the choice not to vaccinate is also a choice to risk COVID-19, so let’s take a look.

When considering whether to vaccinate your child against COVID-19, these considerations related to myocarditis are important:

- Both infection and vaccination have been associated with myocarditis. The rates and severity of myocarditis have been greater following infection compared with vaccination. A review of the literature, published in August 2022, found that an individual was at least 7 times more likely to experience myocarditis resulting from a COVID-19 infection than from COVID-19 vaccination.

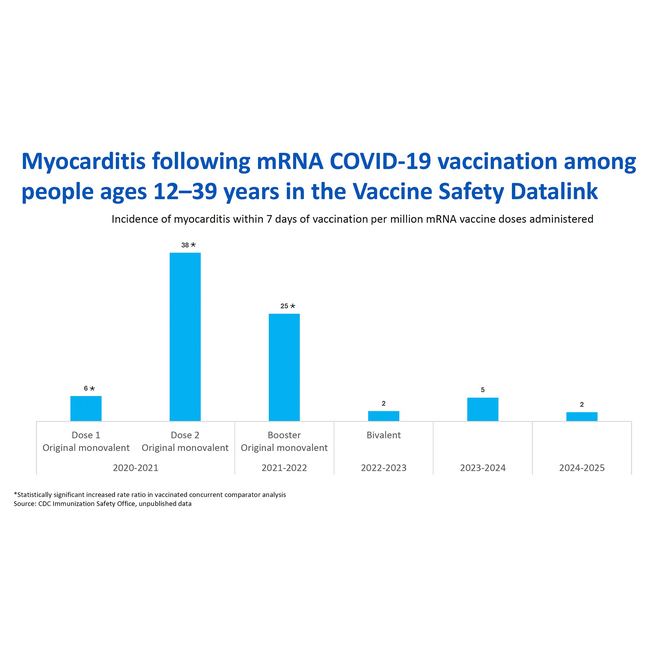

- Over time, the risk for myocarditis following vaccination has decreased as shown on this slide from the April 2025 ACIP meeting. The rate of myocarditis after receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines has not exceeded background rates in the population for the last three seasonal vaccines (beginning with the 2022-2023 version).

- Studies have shown that children younger than 5 years of age do not experience myocarditis following receipt of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, so vaccinating young children before the risk of myocarditis increases is one way to avoid this potential side effect. Importantly, immunization of our youngest population against COVID-19 has been extremely limited, so it is possible that over time, as more youngsters are vaccinated, we would identify a low risk for myocarditis in young children as well. However, it is also possible that we would see a greater risk from infection compared with vaccination. These are the types of information we need to continue working toward understanding when it comes to this disease.

- For those at greater risk of this side effect, increasing the time between doses to at least eight weeks, lessens the risk of this side effect.

Visit the “Myocarditis and COVID-19” section of our Vaccine Safety References webpage to review some of the scientific studies related to this topic.

Last updated: June 25, 2025

Can someone with COVID-19 get the COVID-19 vaccine or booster?

In the U.S., the CDC recommends that anytime someone has a respiratory illness, they try to stay away from others until their symptoms start improving and they have not had a fever for at least 24 hours.

Related to COVID-19 vaccination, people who recently had COVID-19 are recommended to wait for about three months before getting vaccinated because the antibodies from infection offer protection for a few months.

Last updated: June 25, 2025

Why are booster doses recommended?

The goal of vaccination is to prevent serious illness. This is achieved by generating immune memory cells, such as B cells and T cells. These cells are typically long-lived and reside in the bone marrow, bloodstream, and lymph glands to monitor for exposure to a pathogen. If the pathogen is detected, these memory cells quickly become activated and stimulate the immune response to efficiently fight the infection before the infection can get out of control and cause serious illness. In the case of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, studies demonstrated that high levels of memory cells are generated, and as variants emerged, we saw that the levels of memory cells generated by both the mRNA (Pfizer and Moderna) and adenovirus-based (J&J/Janssen) vaccines were sufficient to prevent serious illness in most cases. As such, these findings would not warrant a booster dose.

However, a second goal of vaccination could be to prevent any level of illness, meaning that vaccinated people would not even experience mild or asymptomatic infection. To accomplish this, people need to have high levels of neutralizing antibodies circulating in their bloodstream. Neutralizing antibodies prevent the virus from attaching to and entering cells. Typically, neutralizing antibody levels fade over time. When this happens, a booster dose can stimulate the memory B and T cells to cause production of neutralizing antibodies, thereby increasing the level of detectable antibodies in the bloodstream and decreasing the chance for any level of illness for another brief period (a couple of months).

While prevention of any level of illness is a noble goal, historically, prevention of serious illness has been the goal of vaccination, particularly for respiratory infections, like COVID-19. These two goals have been at the heart of the scientific “debate” over the need for booster doses. In truth, prevention of serious illness is the only reasonable and attainable goal for a virus like SARS-CoV-2, which has a short incubation period.

With this said, people at increased risk for severe COVID-19 can benefit from the short-term protection afforded by neutralizing antibodies that result from booster doses, which is why these individuals continue to be recommended to get booster doses.

Watch this video to hear Dr. Offit talk about the Fall 2023 COVID-19 recommendations.

Last updated: June 25,2025

Who is considered immune compromised when it comes to deciding about COVID-19 vaccines?

People should talk with their healthcare providers to determine whether they are considered moderately or severely immune compromised since each individual is unique.

However, in general, people typically considered moderately or severely immune compromised include the following:

- People currently being treated for cancers of the blood or organs (so-called “solid tumor” cancers)

- People with blood-related cancers, regardless of current treatment status, including those with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma and acute leukemia

- People who received an organ transplant and take immunosuppressive medications to prevent rejection of the organ

- People who had a stem cell transplant or received CAR T-cell therapy less than 2 years ago or who are taking immunosuppressive medications

- People with conditions that are considered to cause permanent immune deficiency because the condition affects cells of their immune system, such as DiGeorge syndrome or Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

- People infected with HIV whose infection is untreated or considered to be at an advanced stage

- People currently being treated with one of the following types of medications:

- High-dose corticosteroids (more than 20 mg prednisone or similar medications per day)

- Alkylating agents

- Antimetabolites

- Transplant-related immunosuppressive medications

- Cancer chemotherapeutic medications that are considered severely immunosuppressive (e.g., tumor-necrosis, or TNF, blockers)

- Biologic agents that suppress or modulate the immune response (e.g., B-cell depleting agents)

Some people 12 years of age and older in these groups may be eligible for ongoing protection through intravenous receipt of a monoclonal antibody product called Pemgarda. Treatments are required every three months. This product cannot be used for treating COVID-19. If you want to find out if you are eligible and could benefit from this product, speak to your healthcare provider who treats you for your immune-compromising condition.

People who should work with their healthcare provider to determine their need for additional doses include:

- People taking medications that make them uncertain whether they would be included in the list of individuals mentioned above

- People with immune-system-related conditions not specifically mentioned above

- People preparing to start one of the above-mentioned medications

People not considered to be in this category include:

- People who do not have compromised immunity.

- People without a spleen.

- People who had cancer but are no longer being treated.

- People with chronic conditions that do not involve the immune system or require treatment with high doses of corticosteroids, such as diabetes, asthma, COPD, kidney disease, heart conditions, sickle cell disease, among others. If you are not sure, check with your healthcare provider.

Last updated: April 24, 2024; reviewed: July 27, 2025

Can people get other vaccines at the same time as their COVID-19 vaccine?

Yes. The COVID-19 vaccine can be administered at the same visit as any other vaccines (including influenza and RSV vaccines as well as nirsevimab, the RSV monoclonal antibody prevention for infants).

One exception, however, is for people, particularly young males, who need both a COVID-19 and an orthopoxvirus (mpox or smallpox) vaccine. These people should consider waiting at least four weeks between receipt of the vaccines due to increased risk of myocarditis.

Vaccines given at the same visit should be given in different locations separated by at least one inch.

Last updated: September 20, 2023; reviewed July 27, 2025

What is the difference between emergency use authorization and the normal process of vaccine approval?

The main difference between emergency use authorization, or EUA, and the normal process, which is via a biologic licensure application, or BLA, is how long data were collected prior to the vaccines being reviewed for use. So, when considered quite literally, the vaccines being used under EUA are no different than those that are used after the vaccines get full approval (BLA). The reason for the shortened timeline for COVID-19 vaccines was, of course, because of the pandemic. But, importantly, steps were not skipped to shorten the timeline, and at this point, these vaccines have been given safely to millions of people, and they have now been licensed.

Last updated: July 27, 2025

Were the COVID-19 vaccines approved by the FDA?

Even though the COVID-19 vaccines were initially released under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), they were still approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The review process was the same, but because of the pandemic, the data could be submitted after a shorter period of participant follow-up than usual. However, even after submitting data (and getting an EUA), those studies continued. At this point, COVID-19 vaccines have been licensed.

Last updated: July 27, 2025

Is it safe for my teen to get the COVID-19 vaccine given the stories about myocarditis?

Cases of myocarditis, or inflammation of the heart, were reported in a small number of people after receipt of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, particularly using the earliest COVID-19 vaccines (2020-2022). While some cases continue to be reported, the rates of myocarditis after receipt of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines have not been greater than background rates of myocarditis for the last three seasons (2022-2023, 2023-2024, and 2024-2025).

- The cases of myocarditis occur more often in boys and young men and more often after the second dose. Symptoms typically occur within 4 days after receipt of the dose. Recently immunized teens and young adults who experience chest pain or shortness of breath should be seen by a healthcare provider and report recent their vaccination.

- Myocarditis is somewhat common, particularly following viral infections. In fact, cases tend to occur more often in the spring due to viruses that circulate at this time of year (specifically, coxsackie B viruses). Typically, about 100-200 cases occur per million people per year.

- Available data suggest that the incidence of myocarditis following mRNA vaccines is about 1 to 10 per 100,000 vaccine recipients; however, this risk increases in males between 16 and 39 years of age to about 1 per 10,000 vaccine recipients. These numbers are lower in females. They are also lower than if people are infected with the virus that causes COVID-19, which increases the risk of myocarditis at least sevenfold.

- Parents and teens should watch for symptoms that may include chest pain, pressure, heart palpitations, difficulty breathing after exercise or lying down, or excessive sweating. One or more of these symptoms may also be accompanied by tiredness, stomach pain, dizziness, fainting, unexplained swelling, or coughing. If a recently vaccinated teen develops these symptoms or you are unsure, contact the child’s doctor or seek more immediate medical assistance if needed.

Find out more in this article from our Vaccine Update newsletter for healthcare providers.

Visit the “Myocarditis and COVID-19” section of our Vaccine Safety References webpage to review some of the scientific studies related to this topic.

Last updated: July 27, 2025

Is it safe for my child to get the COVID-19 vaccine?

Yes. Millions of children and teens have been safely vaccinated against COVID-19, and children can benefit from getting the COVID-19 vaccine if they have not received a COVID-19 vaccine previously. This is also true for children who have had COVID-19 infections, where a COVID-19 vaccine can boost immunity. In 2024-2025, infants less than 6 months of age were hospitalized at rates similar to people between 65 and 74 years of age, and children between 6 months and 23 months were hospitalized at rates similar to adults 50-64 years of age. Likewise, children can suffer lingering effects of their infection, commonly referred to as “long COVID.”

Last updated: July 27, 2025

If my child is near one of the cutoff ages for different doses (5 or 12 years of age), is it better to get them vaccinated or wait?

Since COVID-19 is still circulating and it takes several weeks for a person to be considered fully immunized, it is generally recommended to start the vaccination process with the vaccine the child is currently eligible to receive even if it is a lower dose.

If your child’s birthday occurs during the period between doses, the child will be offered the higher dose for their subsequent doses. Two exceptions are worth noting. First, if your child started with the Pfizer vaccine at age 4 and then turns 5, they will still be given the third dose of the vaccine for younger children (3 micrograms). Second, if your child is moderately or severely immune compromised and they transition from 11 to 12 years of age during their dosing, they may finish with the original doses or the doses for their age. Talk with your child’s healthcare provider if you feel your child might be in this situation.

Last updated: April 24, 2024; reviewed July 27, 2025

What side effects will my child experience from the COVID-19 vaccine?

Side effects in children were similar to what has been found in other age groups, including pain at the injection site, fatigue, headache, fever, chills, muscle pain, or joint pain.

Even though a small number of cases of myocarditis, or heart inflammation, have been identified in teens and young adults, particularly within 4 days of receipt of the second dose of the vaccine, this side effect has not been found in younger age groups, who receive lower doses and rates have not exceeded background rates of myocarditis in older children and young adults for the past three COVID-19 vaccines (since the 2023-2024 version). However, it is still important to monitor for this potential side effect. Chest pain, shortness of breath, or related symptoms should be reported to a healthcare provider.

Other serious side effects have not been identified, nor have long-term effects. Find additional information:

Visit the “Myocarditis and COVID-19” section of our Vaccine Safety References webpage to review some of the scientific studies related to this topic.

Last updated: July 27, 2025

Can the COVID-19 vaccine affect puberty or fertility in my child?

No. The rumors related to COVID-19 vaccines affecting puberty or fertility are unfounded. The mRNA vaccines are processed near the injection site and activated immune system cells travel through the lymph system to nearby lymph nodes. In this manner, they are not traveling to other parts of the body. As such, there would not be a biological reason to expect that maturation or reproductive functionality of either males or females would be negatively affected by COVID-19 vaccination now or in years to follow. Importantly, due to reports of menstrual cycle changes following vaccination, studies have suggested about a one-day difference in menstrual cycles. In addition, several studies have been completed and none revealed any concerning findings related to miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm birth, birth defects, pregnancy or post-delivery complications or outcomes, infant or neonatal outcomes, menstrual irregularities or post-menopausal bleeding.

Watch this short video in which Dr. Paul Offit discusses COVID-19, the vaccines and infertility.

You can read more about fertility and COVID-19 vaccines in this Vaccine Update article.

Visit the “Fertility and COVID-19 vaccines” section of our Vaccine Safety References webpage to review some of the scientific studies related to this topic.

Last updated: January 7, 2025; reviewed July 27, 2025

If I got a COVID-19 vaccine in another country, can I get one in the U.S.?

Individuals vaccinated in another country are recommended to receive one dose of the current COVID-19 vaccine if they have not received an updated version approved by the FDA or WHO and if they are in a group recommended to receive the vaccine. The dose should be administered at least eight weeks after the most previous COVID-19 vaccine. If they received COVID-19 vaccines that are not FDA or WHO approved, the previous doses do not count, and they should be vaccinated according to the schedule for their age group and health status. The first dose should be administered at least 8 weeks after the last COVID-19 vaccine dose.

Young children (6 months to 4 years of age and people who are considered immune compromised should check with a healthcare provider, as the recommendations may vary somewhat for them based on U.S. recommendations for these groups.

Last updated: July 27, 2025

Can I get the COVID-19 vaccine during my menstrual cycle?

Yes. Although minor changes (about one day in length) to the cycle have been observed, women do not need to schedule their COVID-19 vaccine around their menstrual cycle. The reasons for the changes are possibly the result of effects on specific types of immune system cells that are also present in the uterus or hormonal changes associated with the immune response.

Of note, the COVID-19 vaccine is not shed after vaccination, so being around recently vaccinated individuals would not be expected to affect someone’s cycle.

You can read more about menstruation and COVID-19 vaccines in this Vaccine Update article.

Last updated: December 23, 2022; reviewed July 27, 2025

Do the COVID-19 vaccines contain live virus?

The mRNA (Moderna and Pfizer) vaccines do not contain live virus. Each of these contain a single gene from the virus that causes COVID-19. The gene instructs our cells to make the protein, but no other proteins from the virus are made, so whole virus particles are never present. In this manner, people who were vaccinated cannot shed, or spread, the virus to other people as a result of vaccination. If, however, the individual subsequently becomes infected, they can spread the virus during the days before and early during their infection. Of note, the amount of virus shed by vaccinated people quickly decreases, so they generally shed less virus overall compared to unvaccinated, infected individuals. This is also the case for the J&J/Janssen vaccine; however, that version is no longer available in the U.S.

The Novavax vaccine does not contain live virus, either. It delivers the spike protein directly, rather than having our cells make the protein. As such, viral shedding does not occur following receipt of this version.

In this video, Dr. Paul Offit talks about the ingredients used in the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines.

Last updated: September 20, 2023; reviewed July 27, 2025

Do the COVID-19 vaccines cause viral shedding?

Viral shedding occurs when a person is infected with a virus and whole viral particles produced during the infection are transmitted in the individual’s secretions. For viruses that infect the respiratory tract, like COVID-19, these particles are often found in secretions from the nose and mouth, such as saliva or mucus.

Some people wonder whether they can shed the virus as a result of vaccination. In the case of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines approved for use in the U.S., the short answer is no. The same is true of adenovirus-based vaccines (like J&J/Janssen) although this type of COVID-19 vaccine is no longer approved for use in the U.S. In both cases (mRNA- and adenovirus-based vaccines), only the gene for a single protein from the virus that causes COVID-19 – the spike protein – is introduced. As such, whole viral particles are never produced during vaccine processing. Indeed, people are not considered to be infected when they are vaccinated because the virus does not replicate in them. Further, the vaccines are processed near the site of injection, so the spike protein produced during processing would not be found in nasal or oral secretions. As such, they cannot “shed” the single protein either. Likewise, the Novavax vaccine, which delivers the spike protein directly, cannot result in viral shedding.

However, if vaccinated people are infected, the virus will replicate at low levels in their nasal or oral cavity before the immune system stops it. In this scenario, the individual can shed the virus beginning about two days before the start of symptoms and through the first three to four days after symptoms begin.

Read more about viral shedding in this Parents PACK article, “Viral Shedding and COVID-19 — What Can and Can’t Happen."

Last updated: September 20, 2023; reviewed July 27, 2025

How do mRNA vaccines work?

People make mRNA all the time. In our cells, DNA in the nucleus is used to make mRNA, which is sent to the cytoplasm where it serves as a blueprint to make proteins. Most of the time, the proteins that are produced are needed to help our bodies function.

mRNA vaccines take advantage of this process by introducing the mRNA for an important protein from the virus that the vaccine is trying to protect against. In the case of COVID-19, the important protein is the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The mRNA that codes for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is delivered to our muscle cells, which make the protein. The protein is then processed by immune system cells, called dendritic cells, which express the spike protein on the cell surface, travel to a local lymph node, and stimulate other cells of the immune system (B cells) to make antibodies. These antibodies protect us, so that if we are exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in the future, our immune system is ready and we don’t get sick.

The vaccine is processed over a 1- to 2-week period after vaccination during which time the immune response develops. However, the mRNA only directs protein production in the cell for 1 to 3 days before it breaks down. Once it breaks down, the cell stops making the spike protein.

- Watch an animation of how COVID-19 mRNA vaccines work.

- See more about dendritic cells and the adaptive immune system in this animation.

- Watch this short video of Dr. Offit describing how mRNA vaccines work.

Last updated July 29, 2021; reviewed July 27, 2025

How do adenovirus vector vaccines work?

Although COVID-19 adenovirus-based vaccines are no longer used in the U.S., they remain in use in some other countries. These vaccines take advantage of a class of relatively harmless viruses, called adenoviruses. Some adenoviruses cause the common cold, but others can infect people without causing illness. To use these viruses for vaccine delivery, scientists choose types of adenovirus that do not cause illness and to which most people have not been exposed. They alter the virus by removing two of the genes that enable adenovirus to replicate in people, and they replace one of those genes with the one for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

Like human cells, adenoviruses contain DNA as their genetic material. So, when an adenovirus vaccine is administered, it enters muscle cells where it releases the DNA that includes the gene for the spike protein, and the genetic material enters the nucleus of the cell. In the nucleus, the DNA is used to make messenger RNA (mRNA), which is released into the cytoplasm to serve as a blueprint for making proteins. The DNA from the viral vector, however, cannot insert into the cell’s DNA. The mRNA causes the SARS-CoV-2 protein to be produced. Specialized cells of the immune system, called dendritic cells, put pieces of the newly produced SARS-CoV-2 spike protein on their surface and travel to a draining lymph node where they stimulate other cells of the immune system; specifically, B cells that make antibodies, T cells that help B cells make antibodies, and other T cells that can kill virus-infected cells. Antibodies against the spike protein will now prevent the virus from causing an infection in the future.

Watch an animation of how COVID-19 viral vector vaccines work.

Find out more about adenovirus vaccines in this Vaccine Update article, “Getting Familiar with COVID-19 Adenovirus-replication-deficient Vaccines.”

Last updated: September 20, 2023; reviewed July 27, 2025

How does the protein-based vaccine (Novavax) work?

The Novavax COVID-19 vaccine delivers the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein into our muscle. Once in our muscle, immune system cells that circulate throughout our body recognize the protein as foreign and attack it. Specialized immune system cells, called dendritic cells, put pieces of the protein on their surface and travel to nearby lymph nodes to activate other parts of the immune system. It takes about 1 to 2 weeks for the vaccine to be processed. The result is immunologic memory cells that are specialized to recognize the viral spike protein in the event of a future encounter with the virus.

This process takes advantage of our adaptive immune system, which responds to foreign proteins every day. To find out more about this part of our immune system, watch this animation.

Watch this short video of Dr. Offit describing the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine.

Last updated: July 21, 2022; reviewed July 27, 2025

How did the vaccine companies (e.g., Pfizer and Moderna) decide which mRNA to use?

In order for a virus to reproduce and cause infection, it must get into cells and take over the cellular machinery. Because viruses attach to cells using a particular protein on their surface, in this case the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, scientists understood that blocking that attachment would be a direct way to prevent infection. One way to block this attachment is with antibodies that bind to the surface protein. As such, when the genome was published, scientists developing the nucleic acid or protein subunit vaccines (i.e., those that only used part of the virus) chose the gene for the spike protein, anticipating that this would be the most direct route to developing an effective vaccine. Subsequent COVID-19 mRNA vaccines used mRNA for the spike protein from a newer variant of the virus so that the antibodies our immune system produces more closely match the surface protein of the SARS-CoV-2 viruses currently circulating.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

Who should NOT get the COVID-19 vaccine?

A few groups of people either should not get the vaccine or should get a particular version. Likewise, some individuals should consult with their doctor or follow special procedures.

People who should NOT get any COVID-19 vaccine:

- Those younger than 6 months of age.

- People currently or recently experiencing a COVID-19 infection; these people can get vaccinated once they have been without a fever for 24 hours and their primary symptoms have resolved although it is recommended that these individuals wait at least three months to be vaccinated so they develop a more robust immune response to the vaccine dose.

People who cannot get the mRNA vaccine (Pfizer or Moderna), but may be able to get the protein (Novavax) vaccine:

- Anyone with a previous severe allergic reaction (i.e., one that causes anaphylaxis, any reaction that causes swelling that affects the airway (i.e., tongue, uvula, or larynx), or diffuse rash that also involves respiratory surfaces, such as Stevens-Johnson Syndrome) to a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine dose or an mRNA vaccine component.

- Anyone with a known polyethylene glycol (PEG) allergy.

People who cannot get the protein-based vaccine (Novavax), but may be able to get the mRNA (Pfizer or Moderna) vaccine:

- Anyone with a previous severe allergic reaction (i.e., one that causes anaphylaxis), any reaction that causes swelling that affects the airway (i.e., tongue, uvula, or larynx), or diffuse rash that also involves respiratory surfaces, such as Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, to a COVID-19 protein-based vaccine (Novavax) dose or one of its components.

- Anyone with a known polysorbate allergy.

People who may get the vaccine after considering risks and benefits and/or consulting with their healthcare provider:

- Individuals with a history of a non-severe, immediate (within 4 hours) allergic reaction to a previous dose of COVID-19 vaccine. (These individuals should be observed for 30 minutes after receipt of the vaccine.)

- People who have a severe or immediate allergic reaction to one of the types of vaccines and for whom the cause of the reaction is unknown (i.e., which component caused the reaction) should consult an allergist or immunologist to determine whether the individual can get the other version. If they proceed, they should be vaccinated at a location with medical facilities and staff prepared to respond to medical emergencies.

- People who cannot get one type of COVID-19 vaccine may be able to get the other type.

- People who are moderately or severely ill (regardless of whether they have a fever) may delay vaccination until they feel better.

- People with a history of MIS-C or MIS-A should delay vaccination until at least 90 days after diagnosis and they experience a return of normal cardiac function and are considered clinically recovered.

- People who experienced myocarditis or pericarditis within 3 weeks of receipt of COVID-19 vaccine are typically advised not to get additional doses of any COVID-19 vaccine. In some instances, individuals and their healthcare providers may decide to proceed with an additional dose based on the risk-benefit assessment. In this situation, symptoms should have resolved and at least 8 weeks should have passed before any additional doses are administered. Note: This does not apply to people with history of myocarditis or pericarditis unrelated to COVID-19 vaccination (including from COVID-19 infection, prior to COVID-19 vaccination, or more than 3 weeks after COVID-19 vaccination), nor does it apply to people with a history of heart disease.

People who should follow special procedures

- Pregnant people who develop a fever after vaccination should take acetaminophen. (See more in the pregnancy-related questions lower on this page.)

- People treated with convalescent plasma should not receive measles- or varicella-containing vaccines until at least 7 months after receipt of the plasma.

- People with a known COVID-19 exposure can get vaccinated if they don’t have symptoms.

- People with a current COVID-19 infection should wait at least until symptoms resolve but may have a better immune response to the vaccine if they wait at least 3 months after start of symptoms.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

Where can I get the vaccine?

During the 2025-2026 season, it is unclear who will be offering COVID-19 vaccines. As such, we recommend checking for vaccine at your provider’s office, local pharmacies, healthcare facilities, or public health departments. See “Can I get a COVID-19 vaccine this year, and what should I know about the changes to COVID-19 recommendations?” for more details and considerations.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

What are the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine?

Common side effects are caused as part of the immune response to each vaccine.

mRNA vaccines: Older children and adults

Common side effects are caused as part of the immune response to each vaccine.

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Muscle aches

Side effects occurred during the first week after vaccination but were most likely one or two days after receipt of the vaccine. During clinical trials, side effects were more frequent following the second dose and more likely to be experienced by younger, rather than older, adults.

When COVID-19 vaccines first became available, a small number of people who get the mRNA vaccine experience mild, short-lived inflammation of the heart, called myocarditis. About 1 to 10 of every 100,000 mRNA vaccine recipients experienced this condition. It was most likely in adults 39 years and younger and more often in males. During the last three COVID-19 vaccine seasons (2022-2023, 2023-2024, and 2024-2025), the rates of myocarditis after vaccination were no greater in vaccinated people compared with people who did not get the vaccine. However, it is still possible that this side effect could occur, so recently vaccinated individuals should consider this side effect if they experience chest pain or shortness of breath. This condition tends to occur within 4 days of receipt of the second dose, but it can occur after any dose and up to several days after vaccination. Individuals should seek medical care if symptoms develop.

Myocarditis after vaccination tends to resolve within 2-3 weeks and does not cause long-term heart damage. Importantly, COVID-19 infections can also cause myocarditis, and this tends to occur more frequently after infection compared with vaccination. (See “My teen is a student-athlete and already had COVID-19, so does he need the COVID-19 vaccine? We are worried about myocarditis.” on this page for more detailed information.)

Visit the “Myocarditis and COVID-19” section of our Vaccine Safety References webpage to review some of the scientific studies related to this topic.

mRNA vaccines: Children younger than 5 years of age

Young children who received either the Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccine commonly experienced:

- Pain, tenderness, and swelling near the injection site

- Fever

- Irritability

- Decreased appetite

- Fatigue

Older children in this age group, who are better able to communicate what they are feeling, sometimes also experienced headaches, chills, achiness or joint pain, and nausea or vomiting. These effects were somewhat more likely after receipt of the Moderna vaccine, which is a higher dose, but occurred infrequently overall.

Myocarditis was not detected in this age group, either in clinical trials or since the vaccines have been in use; however, because COVID-19 mRNA vaccines are a rare cause of myocarditis in older adolescents and young adults, it is possible that it could be observed in younger children. Experience with these vaccines in older children and adults suggest that the likelihood of myocarditis is significantly lower following vaccination compared with infection. Also, the doses given to this age group are even lower than those given to older children and adults. However, parents and care providers should still monitor their children in the days following vaccination and contact healthcare providers or seek emergency care should concerns arise.

Protein-based vaccine: Adults

The most common side effects from the protein-based vaccine (Novavax) are:

- Injection site pain and less often redness or swelling

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Muscle aches

A small number of cases of myocarditis have occurred in individuals who received this vaccine; however, additional data are necessary to determine the level of risk. Recently vaccinated individuals who have heart-related symptoms should seek medical care.

Adenovirus-based vaccine: Adults

Adenovirus-based vaccines are no longer available in the U.S., but they are still used in some other countries.

The most common side effects from the adenovirus vaccine (Johnson & Johnson/Janssen) are:

- Injection site pain and less often redness or swelling

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Muscle aches

- Fever

Side effects occurred during the first seven to eight days after vaccination but were most likely to occur one or two days after receipt of the vaccine. Side effects were more often experienced by younger, rather than older vaccine recipients.

Two rare, but potentially dangerous conditions, have been identified following receipt of the adenovirus-based vaccines, such as the J&J/Janssen version:

- Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, or TTS, occurs in about 1-2 of every 1 million vaccine recipients and develops up to 3 weeks after getting vaccinated. Individuals between 18 and 64 years of age, both female and male, who got the J&J/Janssen vaccine have experienced this condition; however, women between the ages of 30 and 49 years of age are at the greatest risk. Anyone who got the J&J/Janssen vaccine less than 3 weeks ago should seek medical care if they develop severe headache, shortness of breath, severe abdominal pain, unexplained leg pain, easy bruising, or small red spots on the skin. Anyone seeking medical care with one or more of these symptoms should mention their recent receipt of the vaccine, so healthcare providers can order the appropriate diagnostic tests and treatments.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome, or GBS, occurs in about 1 of every 100,000 vaccine recipients, most often during the first 3 weeks after getting vaccinated. The condition has most often been identified in males between 50 and 64 years of age, but it can occur in females and those 65 years and older on occasion. While rare, most cases have required hospitalization and at least one person has died. Anyone who recently received an adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccine and experiences muscle weakness or paralysis should seek medical treatment and inform the healthcare provider of the recent vaccination. It should also be noted that COVID-19 infection has been associated with GBS; so, natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 also appears to be a rare cause of GBS. Find out more about GBS in this Parents PACK article, “Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) & Vaccines: The Risks and Recommendations.”

Last updated: August 30, 2025

Can I take medicine for the side effects after I get the vaccine?

You can take anti-fever or anti-inflammatory medications if necessary following COVID-19 vaccination, but it is important to know that doing so could diminish the level of immunity that develops. This is true anytime you take these types of medications, whether following vaccination or to treat illness. Generally speaking, the “symptoms” people experience following vaccination or during illness, such as fever, redness at the injection site, or fatigue, are caused by your immune system response. For example, fever is your body turning up its “thermostat” to make the immune system more efficient and the pathogen less efficient. For these reasons, if you are not very uncomfortable, it is better not to take these medications.

Some wonder how long they should wait after vaccination before taking these types of medicines, so their immune response is not affected. As a rule of thumb, the immune response following receipt of the mRNA vaccine develops over a week or two after vaccination and for the adenovirus vaccine, over the course of about four weeks, but the greatest chance of affecting your immune response would be in the first few days after receipt of the vaccine. Indeed, in the adenovirus vaccine studies, about 1 in 4 vaccine recipients took fever-reducing medication (antipyretics), and most people were still protected from severe disease, and all were protected against hospitalization. Responses to the protein-based vaccine (Novavax) develop over a period of a couple of weeks, but side effects, like fever, are most likely in the first couple of days after receipt of the vaccine.

Find out more in this Parents PACK article, "Medications and COVID-19 Vaccines: What You Should Know."

Last updated: April 24, 2024; reviewed August 30, 2025

If I don’t have side effects, does that mean the vaccine did not work?

Many people will get the vaccine and not experience side effects. This does not mean that the vaccine did not work for them. In the clinical trials side effects occurred at varying rates, for example only about 1 to 20 of every 100 people who received the mRNA vaccine had a fever, but we know that the mRNA vaccine worked for more than 90 of every 100 people.

Last updated: March 1, 2021; reviewed August 30, 2025

What are the expected long-term side effects of the vaccination for COVID-19?

- Most negative effects occur within 6 weeks of receiving a vaccine, which is why the FDA asked the companies to provide 8 weeks of safety data after the last dose.

- mRNA vaccines: The mRNA in the vaccine breaks down quickly because our cells need a way to stop mRNA from making too many proteins or too much of a single protein. But, even if for some reason our cells did not breakdown the vaccine mRNA, the mRNA stops making the protein within about a week, regardless of the body’s immune response to the protein.

Read more about COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in this Parents PACK article, “Long-term Side Effects of COVID-19 Vaccine? What We Know.”

Watch a short video of Dr. Paul Offit explaining why COVID-19 vaccines would not be expected to cause long-term side effects.

- Protein-based vaccines: The protein is processed within a few days.

Although no longer available in the U.S., it is worth mentioning that the DNA from adenovirus-based vaccines does not break down as quickly as mRNA. The DNA in the vaccine cannot alter our DNA because a gene for the enzyme integrase is not present. These vaccines are processed within about 4 weeks, so they would not be expected to cause any long-term effects either.

Last updated: September 21, 2023; reviewed August 30, 2025

Should I stop taking my daily dose of aspirin before getting the COVID-19 vaccine?

If your daily dose of aspirin was prescribed by your physician following a stroke or heart attack, we recommend speaking to that doctor about whether to stop taking your medication for a day or two prior to vaccination. If, however, your daily dose of aspirin is because you have risk factors for a stroke or heart attack (such as high blood pressure or high levels of “bad” cholesterol) but have never had a stroke or heart attack, you should talk to your doctor about discontinuing the aspirin not only prior to your COVID-19 vaccine, but all together. The data show that while daily aspirin helps prevent second strokes or heart attacks, it does not help prevent first occurrences, even in people who are at increased risk. Our director, Dr. Paul Offit, carefully reviewed the data related to this topic for his book, Overkill: When Modern Medicine Goes Too Far.

Find out more in this Parents PACK article, "Medications and COVID-19 Vaccines: What You Should Know."

Last updated: Jan. 24, 2022; reviewed August 30, 2025

Can additional doses of the COVID-19 vaccine be from a different company?

Previously unvaccinated children 6 months to 4 years of age and those 5 years and older who are unvaccinated or partially vaccinated AND moderately or severely immune compromised should get all doses of the same brand, except in certain situations. If you are in this group, talk to your healthcare provider to determine the recommendations for your situation.

Those 5 years and older who have completed their initial vaccine series according to the recommendations for their age and immune status can get any brand. For people who are not immune compromised, they are generally considered to have completed their initial series after at least one previous dose. For those who are severely or moderately immune compromised, they are generally considered to have completed their initial series after at least 3 doses of mRNA vaccine or 1 dose of adenovirus- or protein-based vaccine PLUS 1 or more doses of mRNA vaccine. If you are unsure of whether you can switch brands based on your vaccination history, talk to your healthcare provider to help determine the recommendation for your situation.

Last updated: September 21, 2023; reviewed August 30, 2025

How long do I need to wait if I had or need to get a non-COVID-19 vaccine?

In most cases, individuals do not need to delay receipt of COVID-19 vaccine and other vaccines; however, if given during the same appointment, the vaccines should be administered in different locations (different arms or separated by at least one inch on the same arm).

The one exception is that people who need to get both an orthopoxvirus vaccine (mpox/smallpox) and a COVID-19 vaccine, particularly teen and young adult males, should consider waiting for 4 weeks between receipt of the two vaccines due to known or potential risks of myocarditis related to individual orthopox and COVID-19 mRNA and protein-based vaccines. However, if the individual is at risk for mpox due to an outbreak or exposure or at risk for severe COVID-19, they should not delay their vaccination given that they would be trading a real risk for a theoretical risk by delaying.

Last updated: September 21, 2023; reviewed August 30, 2025

What is multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C or MIS-A)?

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome can occur in children (MIS-C) or adults (MIS-A). Development of symptoms typically occurs about 4 to 6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection and can occur even in those who did not experience symptoms of COVID-19. Often multiple organs and body systems are involved, including effects on the gastrointestinal tract, heart, kidneys, skin, lungs, and eyes. Individuals with unexplained rash, vomiting or diarrhea, shortness of breath or chest pain or palpitations should seek medical care. Some people with MIS-C or MIS-A will require admission to intensive care and a small number may require mechanical ventilation.

Importantly, rates of this syndrome following COVID-19 infections have declined over time.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

What is long COVID?

Long COVID, also known as post-COVID conditions or long-term COVID, is characterized by long-lasting symptoms related to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Symptoms can last for weeks or months after viral clearance and resolution of the initial infection. Examples of the types of symptoms that affected individuals report include fatigue, difficulty thinking or concentrating (“brain fog”), headache, change in or loss of taste or smell, dizziness, heart palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, joint or muscle pain, anxiety, depression, sleep problems, feelings like “pins and needles,” diarrhea or stomach pain, rash, changes in menstrual cycle, or fever. Symptoms sometimes appear or worsen after physical or mental activity. People, particularly those who experienced severe COVID-19 infections, may also develop new chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart conditions or neurological conditions.

Scientists continue to research long COVID. Current theories about the causes include:

- Long-term SARS-CoV-2 replication or reactivation of other viruses that remain in the body from previous infections

- Changes to the immune system’s ability to self-regulate after infection with the virus

- Tissue damage and dysfunction, such as from small blood clots (specifically microclots) caused by infection in an array of body organs

- Reactivation of other viruses that were living in the person’s cells, such as viruses from the Herpes family, like Epstein-Barr virus.

Watch this video from the American Medical Association for more information about long COVID.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

Does a vaccinated person present a risk to an unvaccinated person?

Vaccinated people do not shed virus following vaccination. COVID-19 vaccines do not contain live viruses, nor do they cause production of whole viral particles. As such, there is no infectious virus to spread from a vaccinated person to someone else.

But a vaccinated person can still be infected and potentially spread the virus to others. If they do not have symptoms, they may spread the virus without even knowing they are infected. While vaccinated individuals who become infected can be a source of viral spread, they do not appear to spread as much virus as unvaccinated individuals who become infected because their immune response is able to respond to the infection more quickly – shortening the length of infection and, therefore, the amount of virus produced.

Read more, “Vaccinated or Unvaccinated: What You Should Know.” English | Spanish

Last updated: September 21, 2023; reviewed August 30, 2025

What ingredients are in the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine?

The mRNA vaccines include:

- mRNA – The mRNA is for the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The version known as Mnexspike contains mRNA for only two parts of the spike protein, rather than the whole spike protein. The parts of the spike protein are known as the receptor binding domain (RBD) and the N-terminal domain (NTD).

- Lipids - These are molecules that are not able to dissolve in water. They protect the mRNA, so that it does not break down before it gets into our cells. These can be thought of as little “bubbles of fat,” which surround the mRNA like a protective wall. The lipids are the most likely components of the vaccine to cause allergic reactions.

- Salts and amines - Salts and amines are used to keep the pH of the vaccine similar to that found in the body, so that the vaccine does not damage cells when it is administered.

- Sugar – This ingredient is literally the same as that which you put in your coffee or on your cereal. It is used in both of the vaccines to help keep the “bubbles of fat” from sticking to each other or to the sides of the vaccine vial.

These are the only ingredients in the mRNA vaccines. You can see COVID-19 vaccine ingredients on this page of our website.

NOT in the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines:

- Animal Products

- Antibiotics

- Blood products

- DNA

- Egg Proteins

- Fetal material

- Gluten

- Microchips

- Pork products

- Preservatives, like thimerosal

- Soy

Note: The trace quantities of small DNA fragments, which are contained in several biologics, including other vaccines, are well within the levels established as safe by the FDA. To find out more about DNA fragments, see “Do DNA fragments in COVID-19 mRNA vaccines cause harm?” at the beginning of this page. You can see the ingredients in all COVID-19 vaccines on this page of our to see how our cells are equipped to manage the fragments of DNA that we are exposed to throughout our lives.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

What ingredients are in the COVID-19 adenovirus-based vaccine?

Adenovirus-based vaccines are no longer available in the U.S.; however, they are used in other countries.

The adenovirus vaccine includes:

- Adenovirus type 26 (Ad26) containing SARS-CoV-2 spike protein gene and altered so that it cannot replicate

- Stabilizers – Salts, alcohols, polysorbate 80, and hydrochloric acid

- Manufacturing by-products – amino acids

Because the adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccine is grown in fetal cells and although the product is highly purified, remnants of the fetal cells may remain in the final product.

NOT in the COVID-19 adenovirus vaccines:

- Animal Products

- Antibiotics

- Blood products

- Egg Proteins

- Gluten

- Microchips

- Pork products

- Preservatives, like thimerosal

- Soy

Last updated: September 21, 2023; reviewed August 30, 2025

What ingredients are in the COVID-19 protein-based vaccine (Novavax)?

The protein-based vaccine includes:

- SARS-CoV-2 spike protein from SARS-CoV-2 virus

- An adjuvant derived from the soap bark tree (Quillaja saponaria), called Matrix-M

- Stabilizers – Salts (including table salt), polysorbate 80, and hydrochloric acid

You can see the ingredients in all COVID-19 vaccines on this page of our website.

NOT in the COVID-19 protein-based vaccine:

- Animal Products

- Antibiotics

- Blood products

- DNA

- Egg Proteins

- Fetal material

- Gluten

- Microchips

- Pork products

- Preservatives, like thimerosal

- Soy

Watch this short video of Dr. Offit describing the Novavax COVID-19 vaccine.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

Do COVID-19 vaccines contain antibiotics?

No. COVID-19 vaccines do not contain antibiotics.

See the ingredients in COVID-19 vaccines on this page of our website.

Last updated: September 21, 2023; reviewed August 30, 2025

Can mRNA vaccines change the DNA of a person?

Since mRNA is active only in a cell’s cytoplasm and DNA is located in the nucleus, mRNA vaccines do not operate in the same cellular compartment that DNA is located.

Further, mRNA is quite unstable and remains in the cell cytoplasm for only a limited time (See “What stops the body from continuing to produce the COVID-19 spike protein after getting an mRNA vaccine?” below.) mRNA never enters the nucleus where the DNA is located, so it can’t alter DNA. For more details, see “Do DNA fragments in COVID-19 mRNA vaccines cause harm?” at the beginning of this page.

Last updated: April 24, 2024; reviewed August 30, 2025

Can adenovirus-based vaccines change the DNA of a person?

Although adenovirus-based vaccines are no longer available in the U.S., they are still used in some other countries and some people in the U.S. received them previously, so it is useful to know that they cannot change a person’s DNA. Adenovirus-based vaccines contain DNA, which enters the nucleus of cells after vaccination, but the virus cannot replicate and the vaccine does not include a necessary enzyme, called integrase. Therefore, the vaccine cannot change a person’s DNA.

Last updated: September 21, 2023; reviewed August 30, 2025

What stops the body from continuing to produce the COVID-19 spike protein after getting a COVID-19 mRNA or adenovirus-based vaccine?

Both the mRNA and adenovirus vaccines result in production of spike protein that results from mRNA blueprints. Because our cells are continuously producing proteins, they need a way to ensure that too many proteins do not accumulate in the cell. So, generally speaking, mRNA is always broken down fairly quickly. Even if for some reason our cells did not breakdown the vaccine mRNA, the mRNA stops making the protein within about a week, regardless of the body’s immune response to the protein. Once the mRNA is broken down, the blueprint is gone, so the cell can no longer continue to make spike proteins.

Likewise, while the adenovirus-based vaccine delivers DNA and the DNA lasts longer than mRNA, studies have shown that adenovirus-based DNA does not last longer than a few weeks.

For more details on the process by which spike protein production is limited, see the “mRNA vaccine” section of this article.

Last updated March 28, 2023; reviewed August 30, 2025

Will the spike protein from current vaccines cause an issue if there are future variants?

No. The spike protein does not remain in the body for an extended time, nor does it travel around the body. The only thing that remains after the vaccine is processed are antibodies and memory immune cells. Previous vaccination against COVID-19 has produced immunologic memory that remains effective against newer variants and has not caused concerns.

Last updated: August 30, 2025

Is it okay to donate blood after getting the COVID-19 vaccine?

Giving blood after getting the COVID-19 vaccine will not diminish the resulting immune response, which mostly builds in the lymph nodes near the injection site. Likewise, the American Red Cross (ARC) does not require a delay following vaccination with the vaccines currently approved for use in the U.S.; however, individuals must know which brand of vaccine they received and show the immunization card if possible. More details about blood donation are available on the ARC website.

Last updated: March 18, 2021; reviewed August 30, 2025

Are COVID-19 vaccines made in fetal cells?