What is anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA)?

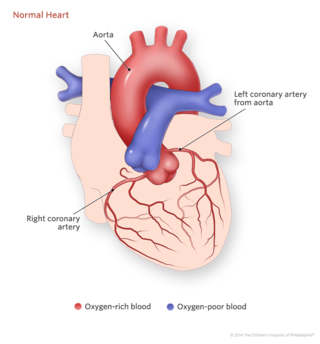

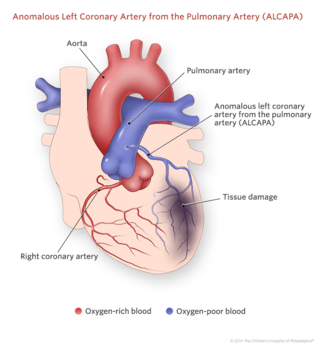

In a normal heart, both coronary arteries arise (branch) from the aorta. In anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA), the left coronary artery arises from the pulmonary artery instead of the aorta. Sometimes doctors call this heart defect “anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery.” Anomalous means atypical. Most children with this condition present in the first year of life.

When the left coronary artery is attached to the pulmonary artery instead of the aorta, two main differences in the blood flow feeding the heart occur that can quickly cause the tissue of the heart to become damaged and die:

- Not enough blood reaches the heart because of “coronary steal.” When the left coronary artery is attached to the pulmonary artery, some of the blood flowing into the coronary artery never makes it to the heart. Instead, it flows back into the pulmonary artery, which “steals” the blood from the heart.

- The blood that does reach the heart doesn’t have as much oxygen as it should. Because in ALCAPA the left coronary artery arises from the pulmonary artery, it supplies the heart muscle with deoxygenated (blue) blood. When there is less overall oxygen in the blood, the heart muscle receives less oxygen to send to the heart cells.

The combination of “coronary steal” plus lower blood oxygen leads to the starvation of the heart muscle, which can cause heart muscle damage or death.

Signs and symptoms of ALCAPA

In an infant, ALCAPA symptoms can include:

- Blue or purple tint to gums, tongue, skin and nails (cyanosis)

- Poor eating and poor weight gain

- Crying with feeds

- Rapid breathing or shortness of breath

- Profuse sweating, especially with feeding

- More sleepiness than normal

- Unresponsiveness (the baby seems “out of it”)

- Heart murmur - the heart sounds abnormal when listening with a stethoscope

Testing and diagnosis for anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery

ALCAPA cannot be detected during pregnancy. ALCAPA is usually diagnosed in infancy, after a parent or pediatrician notices symptoms. In rare cases, the child doesn’t have noticeable ALCAPA symptoms until they are a toddler or older.

Diagnostic testing of ALCAPA may include:

- Chest x-ray. This usually shows an enlarged heart.

- Echocardiogram (also called “echo” or ultrasound) – sound waves create an image of the heart. This may provide the definitive diagnosis if the coronary arteries are able to be fully visualized.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG) – a record of the electrical activity of the heart. This may show evidence of myocardial infarction (heart attack).

- Cardiac MRI – a three-dimensional image shows the heart's abnormalities.

- In many cases cardiac catheterization will also be required. In a cardiac catheterization, a thin tube is inserted into the heart through a vein and/or artery in the leg. This tube, or catheter, makes measurements throughout the heart and with the use of contrast, can better visualize the coronary anatomy.

Treatments for ALCAPA

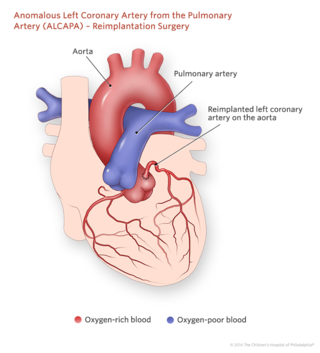

Surgery is required to repair ALCAPA. Your child’s team will discuss the various surgical procedures that can be used, including:

- Detaching the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery and suturing (stitching) it into the correct position on the aorta.

- Creating a tunnel from the aorta to the anomalous left coronary artery, and then closing the connection between the left coronary artery and the pulmonary artery.

- Removing the faulty left coronary artery, then using a vein from the leg to create a new left coronary artery.

- Creating a connection between the left subclavian artery (a large artery that carries blood to the left arm and upper body) and the left coronary artery. This allows some of the very oxygen-rich blood from the subclavian artery to feed the left coronary artery and the heart.

Outlook for ALCAPA

After surgery, most patients with ALCAPA will experience a good quality of life. Many children who were born with ALCAPA do very well and don’t have any restrictions on school, activity or sports, though they all will need life-long care by a cardiologist. Some will have to remain on medicine, but many will be able to stop taking medicines within weeks or months of surgery.

Follow-up care for anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery

Through age 18

Follow-up appointments with a cardiologist will be required after the surgery, to make sure the child’s heart is working properly.

As the child grows, a cardiologist will continue to monitor the heart, at annual appointments or more frequently if required. Children who are born with ALCAPA will require life-long care by a cardiologist, because they are at higher risk for abnormal heart rhythms.

Into adulthood

Once children are older than 18 years, they will transfer to an adult cardiologist. The Philadelphia Adult Congenital Heart Center, a joint program of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Penn Medicine, meets the unique needs of adults who were born with heart defects.

Why Choose Us

Our specialists are leading the way in the diagnosis, treatment and research of congenital and acquired heart conditions.

Resources to help

Cardiac Center Resources

We know that caring for a child with a heart condition can be stressful. To help you find answers to your questions – either before or after visiting the Cardiac Center – we’ve created this list of educational health resources.

Reviewed by Victoria L. Vetter, MD, FAAP, FACC

Reviewed on 10/23/2024