Experimental Gene Therapy for Hemophilia B: Jay’s Story

Experimental Gene Therapy for Hemophilia B: Jay’s Story

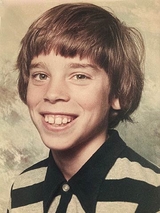

Hemophilia B, the blood disorder Jay was born with, affected many aspects of his life. He spent his entire childhood going to hospitals to get treated. “It was horrible for a kid,” he says. As an adult, he lived what he considers a normal life, but “with interruptions when I’d injure myself.” Now 58, Jay’s life was transformed by his participation in a trial for an experimental, potentially curative gene therapy for hemophilia B developed at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). It has made his need for treatment almost disappear.

Hemophilia B is most often caused by an inherited gene mutation that impairs a person’s ability to produce normal levels of a blood clotting factor called factor IX. Without this clotting factor, a person can experience debilitating or life-threatening bleeding, either caused by an injury or occurring spontaneously. Routine activities have the potential to cause prolonged bleeding, either externally or internally, often in the joints and muscles.

Jay’s older brother was born with the disease, so when Jay was born, the doctors in Ontario, Canada, where the family lived, knew to check for it. At age 1, he began receiving clotting factors derived from plasma, which was administered intravenously in a hospital. The next treatment development was long-acting factor IX, which still required hospital visits. It wasn’t until he was nearly 18 years old that a factor IX product was developed that could be stored and administered at home via injection.

Hemophilia a risk that ‘is always there’

During his childhood, he says that his mother “was everything — it must have been so tough for her.” If he would get injured on the school playground or during sports, “I was all about hiding my injuries from my mother. When I got injured, my brother was my support. I would hide it because I dreaded going to the hospital. It was all very traumatic.”

Overall, however, Jay considers himself lucky: He never had a life-threatening episode. As he got older, he attended university and studied aerospace engineering. The repercussions of one injury caused him to miss a month of classes, but he graduated on time and had one job for most of his life at an aerospace company, where he rose to vice president. The hemophilia never affected him at work because of the treatment available — injections of factor IX that could be self-administered regularly or when needed after an injury.

He knew, however, that with the disease, “risk is always there. All it takes is bumping your head and not having treatment nearby.” He thinks about his early teenage years when he played on a baseball team. “I loved baseball, but I ended up realizing that even with baseball there were too many opportunities to get injured. The older you got, the more competitive it got, and the pitcher threw the ball harder.” His main exercise routine became swimming and cycling.

Hospitalized after an injury

A shift in his outlook occurred in December 2013, when he injured himself while shoveling snow. “I treated myself, but a week later it got really bad, the worst injury I’ve ever had, and I ended up in the hospital for the first time in my life.” He was hospitalized for 10 days. “It was three months before I could walk using a cane, and another three months until I could walk solo. It was a very bad experience.”

Two years later, his hematologist informed him about a game-changing opportunity: an experimental gene therapy available through a clinical trial at CHOP. Jay was aware of the existence of gene therapies, but this one seemed like “a quantum shift — you just need to put it in your body once.” Indeed, this gene therapy for hemophilia B involves a one-time infusion that delivers a functional gene to replace the patient’s own defective gene. The result is better clotting factor activity to protect against bleeding.

His immediate thought when hearing this was available? “Sign me up!” Going to Philadelphia was “the best time of my life,” he says. “The environment at CHOP is like 23rd-century stuff. It’s really cool. It was a total joy.”

‘I have to remind myself I don’t have to worry’

He received the gene therapy from the team that has now formed CHOP’s recently launched Novel Therapeutics for Bleeding Disorders (NoT Bleeding) Program. This team includes world-class experts in hemophilia gene therapy and the management of bleeding disorders.

Since receiving the gene therapy in 2016, Jay’s need for treatment has been essentially eliminated. When asked what that feels like, he says, “The absence of a bad thing is hard to describe. It made me reflect on how much having hemophilia shaped who I am. Now if I injure myself, I forget that it might cause me a problem. In the past I would run home for treatment. I have to remind myself I don’t have to worry about it.” For him, this reduced worrying is “bigger than anything else.”

Would he do the experimental therapy again? “A million times over.”