Case

A 4-month-old infant, L.M., was referred by her pediatrician to Otolaryngology (ENT) at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) for an evaluation of noisy breathing and GERD. After scheduling an evaluation, L.M. had 2 episodes of apnea resulting in blue spells while feeding. Her mother placed a follow-up call to ENT and was advised to take L.M. to the Emergency Department (ED). L.M.’s parents brought her to their local ED and she was subsequently transferred to CHOP. In the CHOP ED, an ENT consult with nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy (NPL) revealed laryngomalacia and signs of gastro-esophageal reflux. Recommendations included an expedited appointment with Gastroenterology (GI) for optimization of GER management and follow-up with ENT in 2 months for surveillance of laryngomalacia. L.M.’s family was also instructed to call ENT if symptoms worsened or if she had any witnessed apneic episodes.

Two weeks after evaluation in the ED, she returned for an evaluation with Matthew Ryan, MD, in GI. L.M. continued with symptoms despite starting thickened feeds; and in fact, thickened feeds resulted in worsened breathing difficulty. An evaluation of swallow dysfunction via video fluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) was ordered. A VFSS is a radiographic study to evaluate oral, pharyngeal and esophageal function during swallowing. The VFSS revealed severe pharyngeal dysphagia with delayed swallow initiation and silent aspiration (passage of materials past the vocal cords into the airway without a cough response) of thin and honey-thick liquid. The speech-language pathologist (SLP) was unable to make a recommendation for a safe oral feeding plan given the severity of L.M.’s dysphagia. Therefore, she was directly admitted to the GI service at CHOP to initiate nonoral means of nutrition.

Triple scope needed to diagnosis LTEC

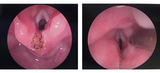

During L.M.’s inpatient stay a variety of tests were completed to determine the etiology of her dysphagia and further evaluate her airway. The GI medical team ordered an esophagram to evaluate for a tracheoesophageal structure or fistula. ENT, Speech Therapy, and Pulmonary were consulted. A triple scope with ENT (microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy), Pulmonary (flexible bronchoscopy with BAL), and GI (esophagogastroduodenoscopy) was completed and revealed tracheomalacia, abundant watery secretions (likely aspirated saliva), and a deep inter-arytenoid groove at least to the level of the true vocal cords consistent with a type 1 laryngotracheal-esophageal cleft (LTEC) (Figure 1). Initially speech therapy had recommended initiating a very conservative plan of small tastes of pureed baby food in order to maintain oral skills. However, after the findings of a type 1 LTEC, the decision was made that L.M. should not engage in any oral feeding and all nutrition was given via nasogastric tube. After discharge, L.M. followed up for a multidisciplinary visit with ENT, Pulmonary, GI and speech therapy in the Aerodigestive Program and Steven E. Sobol, MD, MSc, from ENT made plans to repair her type 1 LTEC.

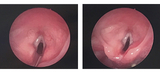

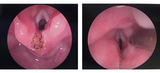

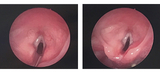

Her LTEC repair was performed 8 weeks after her initial presentation to ENT (Figure 2). L.M. was continued on nasogastric feeds after her surgery until re-evaluation. Two weeks after L.M.’s LTEC repair a repeat microlaryngoscopy bronchoscopy (MLB) was conducted (Figure 3). The laryngeal cleft site was intact with no residual cleft noted. A repeat VFSS was ordered and completed 2 weeks later. The swallow study showed improvement in swallow function, but there was continued dysphagia with delayed swallow initiation and frequent laryngeal penetration (passage of material in the larynx with redirection into the esophagus) without aspiration into the upper airway. The SLP recommended initiation of a small volume of honey-thick liquids via bottle and spoon feeding of puree with a follow-up feeding evaluation in 2 weeks. At her SLP visit 2 weeks later, L.M. was a full oral feeder doing well on thickened feeds and purees. The SLP set-up a plan for a gradual wean of thickened liquids over 6 weeks to slowly transition her off thickened liquids. L.M. is doing great with her feeding at home!

Case Discussion

What is a laryngeal cleft?

Laryngotracheal-esophageal cleft (LTEC) is a rare congenital defect in which there is a posterior communication between the larynx and the pharynx, and possibly involving the trachea and the esophagus. The airway and esophagus originate from a common tube called the foregut. Early in embryologic development, the airway separates from the esophagus with the formation of the tracheoesophageal septum. LTEC is thought to occur when the septum does not completely develop, resulting in variable degrees of communication between the airway and esophagus. LTEC may be associated with other midline defects such as tracheoesophageal fistula, cleft lip/palate, and heart defects.

- Type 1 cleft – extends through the interarytenoid muscles but spare the cricoid cartilage

- Type 2 cleft – extends through the cricoid cartilage

- Type 3 cleft – extends through the upper trachea

- Type 4 cleft – extension into the thoracic portion of the trachea and may be incompatible with long-term survival

What are signs and symptoms of a laryngeal cleft?

Patients with laryngeal cleft often present with feeding difficulties. Other symptoms may depend on the severity of their cleft and can include: chronic cough, aspiration, recurrent respiratory infections, recurrent pneumonia, stridor and other midline anomalies.

When to refer?

Infants with suspicion of laryngeal cleft need to be evaluated for airway, feeding, and pulmonary issues. Coordination of care with ENT, GI, SLP, and Pulmonary services is important for medical and surgical management. These children may also need evaluation by other services such as Cardiology, Ophthalmology and Genetics.

In milder cases where the child is not experiencing respiratory distress, a patient may initially be managed with close observation by ENT, reflux management by GI, and thickened feeds under guidance of speech-language therapist. If the child is not showing improvement with optimizing medical management, they should be referred to the Aerodigestive Program in the Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders.

In more severe cases, and in cases where medical optimization does not show improvement, the child needs aerodigestive evaluation and a triple scope. A triple scope involves evaluation of airway, lungs, and GI tract with a microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy by ENT, a flexible bronchoscopy with BAL by Pulmonary, and esophagogastroduodenoscopy by GI. These children often need a feeding tube.

Finally, repair is considered after confirming diagnosis of a laryngeal cleft. Surgery should be performed as soon as possible to avoid long-term complications from aspiration and limited oral feeding. The goal of surgery is to repair the communication between the airway and esophagus to stop aspiration. The long-term goal is to allow these children to resume oral feeding.

Type 1 LTEC is often repaired endoscopically. Type 2 LTEC may be repaired endoscopically or may require open repair through the neck. Type 3 and 4 LTEC require open repair and often a tracheostomy tube. Despite treatment, Type 4 LTEC is often associated with poor long-term survival.

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

Case

A 4-month-old infant, L.M., was referred by her pediatrician to Otolaryngology (ENT) at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) for an evaluation of noisy breathing and GERD. After scheduling an evaluation, L.M. had 2 episodes of apnea resulting in blue spells while feeding. Her mother placed a follow-up call to ENT and was advised to take L.M. to the Emergency Department (ED). L.M.’s parents brought her to their local ED and she was subsequently transferred to CHOP. In the CHOP ED, an ENT consult with nasopharyngeal laryngoscopy (NPL) revealed laryngomalacia and signs of gastro-esophageal reflux. Recommendations included an expedited appointment with Gastroenterology (GI) for optimization of GER management and follow-up with ENT in 2 months for surveillance of laryngomalacia. L.M.’s family was also instructed to call ENT if symptoms worsened or if she had any witnessed apneic episodes.

Two weeks after evaluation in the ED, she returned for an evaluation with Matthew Ryan, MD, in GI. L.M. continued with symptoms despite starting thickened feeds; and in fact, thickened feeds resulted in worsened breathing difficulty. An evaluation of swallow dysfunction via video fluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) was ordered. A VFSS is a radiographic study to evaluate oral, pharyngeal and esophageal function during swallowing. The VFSS revealed severe pharyngeal dysphagia with delayed swallow initiation and silent aspiration (passage of materials past the vocal cords into the airway without a cough response) of thin and honey-thick liquid. The speech-language pathologist (SLP) was unable to make a recommendation for a safe oral feeding plan given the severity of L.M.’s dysphagia. Therefore, she was directly admitted to the GI service at CHOP to initiate nonoral means of nutrition.

Triple scope needed to diagnosis LTEC

During L.M.’s inpatient stay a variety of tests were completed to determine the etiology of her dysphagia and further evaluate her airway. The GI medical team ordered an esophagram to evaluate for a tracheoesophageal structure or fistula. ENT, Speech Therapy, and Pulmonary were consulted. A triple scope with ENT (microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy), Pulmonary (flexible bronchoscopy with BAL), and GI (esophagogastroduodenoscopy) was completed and revealed tracheomalacia, abundant watery secretions (likely aspirated saliva), and a deep inter-arytenoid groove at least to the level of the true vocal cords consistent with a type 1 laryngotracheal-esophageal cleft (LTEC) (Figure 1). Initially speech therapy had recommended initiating a very conservative plan of small tastes of pureed baby food in order to maintain oral skills. However, after the findings of a type 1 LTEC, the decision was made that L.M. should not engage in any oral feeding and all nutrition was given via nasogastric tube. After discharge, L.M. followed up for a multidisciplinary visit with ENT, Pulmonary, GI and speech therapy in the Aerodigestive Program and Steven E. Sobol, MD, MSc, from ENT made plans to repair her type 1 LTEC.

Her LTEC repair was performed 8 weeks after her initial presentation to ENT (Figure 2). L.M. was continued on nasogastric feeds after her surgery until re-evaluation. Two weeks after L.M.’s LTEC repair a repeat microlaryngoscopy bronchoscopy (MLB) was conducted (Figure 3). The laryngeal cleft site was intact with no residual cleft noted. A repeat VFSS was ordered and completed 2 weeks later. The swallow study showed improvement in swallow function, but there was continued dysphagia with delayed swallow initiation and frequent laryngeal penetration (passage of material in the larynx with redirection into the esophagus) without aspiration into the upper airway. The SLP recommended initiation of a small volume of honey-thick liquids via bottle and spoon feeding of puree with a follow-up feeding evaluation in 2 weeks. At her SLP visit 2 weeks later, L.M. was a full oral feeder doing well on thickened feeds and purees. The SLP set-up a plan for a gradual wean of thickened liquids over 6 weeks to slowly transition her off thickened liquids. L.M. is doing great with her feeding at home!

Case Discussion

What is a laryngeal cleft?

Laryngotracheal-esophageal cleft (LTEC) is a rare congenital defect in which there is a posterior communication between the larynx and the pharynx, and possibly involving the trachea and the esophagus. The airway and esophagus originate from a common tube called the foregut. Early in embryologic development, the airway separates from the esophagus with the formation of the tracheoesophageal septum. LTEC is thought to occur when the septum does not completely develop, resulting in variable degrees of communication between the airway and esophagus. LTEC may be associated with other midline defects such as tracheoesophageal fistula, cleft lip/palate, and heart defects.

- Type 1 cleft – extends through the interarytenoid muscles but spare the cricoid cartilage

- Type 2 cleft – extends through the cricoid cartilage

- Type 3 cleft – extends through the upper trachea

- Type 4 cleft – extension into the thoracic portion of the trachea and may be incompatible with long-term survival

What are signs and symptoms of a laryngeal cleft?

Patients with laryngeal cleft often present with feeding difficulties. Other symptoms may depend on the severity of their cleft and can include: chronic cough, aspiration, recurrent respiratory infections, recurrent pneumonia, stridor and other midline anomalies.

When to refer?

Infants with suspicion of laryngeal cleft need to be evaluated for airway, feeding, and pulmonary issues. Coordination of care with ENT, GI, SLP, and Pulmonary services is important for medical and surgical management. These children may also need evaluation by other services such as Cardiology, Ophthalmology and Genetics.

In milder cases where the child is not experiencing respiratory distress, a patient may initially be managed with close observation by ENT, reflux management by GI, and thickened feeds under guidance of speech-language therapist. If the child is not showing improvement with optimizing medical management, they should be referred to the Aerodigestive Program in the Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders.

In more severe cases, and in cases where medical optimization does not show improvement, the child needs aerodigestive evaluation and a triple scope. A triple scope involves evaluation of airway, lungs, and GI tract with a microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy by ENT, a flexible bronchoscopy with BAL by Pulmonary, and esophagogastroduodenoscopy by GI. These children often need a feeding tube.

Finally, repair is considered after confirming diagnosis of a laryngeal cleft. Surgery should be performed as soon as possible to avoid long-term complications from aspiration and limited oral feeding. The goal of surgery is to repair the communication between the airway and esophagus to stop aspiration. The long-term goal is to allow these children to resume oral feeding.

Type 1 LTEC is often repaired endoscopically. Type 2 LTEC may be repaired endoscopically or may require open repair through the neck. Type 3 and 4 LTEC require open repair and often a tracheostomy tube. Despite treatment, Type 4 LTEC is often associated with poor long-term survival.

Contact us

Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders