Case

E.S., a 23-day-old female, was referred to our Pediatric Otolaryngology service for evaluation of noisy breathing. Her pediatrician, Kristen Danley, MD, reported intermittent inspiratory stridor was noted in the first 2 weeks after birth. Due to concerns for choking and gasping with feeds that could suggest a more significant laryngomalacia, E.S. was referred for an otolaryngology evaluation.

E.S.’s parents reported a history of an intermittent “high pitched” sound on inspiration beginning shortly after birth, worse when feeding and sleeping. History was negative for voice concerns, cyanosis or obstructive pauses during sleep. Occasional spitting up was noted after feeds. E.S. was born at term by vaginal delivery to a healthy G1P1 mother. Her birth was uneventful with Apgar scores of 8 and 9. Her birth weight was 3.5 kg (69%ile). On exam, E.S. was well-appearing, alert, and in no distress. High-pitched inspiratory stridor was noted without retractions. Flexible laryngoscopy demonstrated short aryepiglottic folds with redundant soft-tissue hooding over the vocal folds, consistent with laryngomalacia. We advocated a conservative “wait and see” approach.

One month following her initial visit, Danley called, concerned that E.S. was not growing, was tachypneic with feeds, stridulous, and had moderate retractions at rest. E.S. came weekly for weight checks, and besides other symptoms, Danley noted that E.S. fatigued easily with feedings, not taking greater than 2 oz at a time. Danley switched Ella from breast to bottle, initiated Ranitidine, and referred her to Gastroenterology.

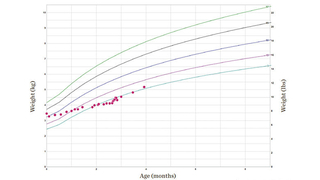

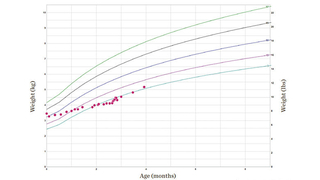

On Otolaryngology follow-up, E.S. was noted to have increased stridor and work of breathing. Her weight was 4.1 kg (1%ile). (See Figure 3.) After discussion with Danley and the family, the shared decision was made to admit Ella to CHOP for nasogastric tube feeding and proceed with supraglottoplasty to surgically correct her laryngomalacia. Surgery was performed without complication, and E.S.’s symptoms resolved over the next 2 days. She was discharged on post-op day 3 and the NG tube removed shortly thereafter. At 1 month follow-up, she was asymptomatic and her weight had increased to 5.2 kg (5%ile).

Discussion

Laryngomalacia is by far the most common diagnosis made in infants with noisy breathing. It is estimated that 60% of infant stridor is attributable to laryngomalacia, although that number is probably an underestimate given that many patients are probably not referred for evaluation of mild symptoms. Most patients with laryngomalacia are born without complication and are discharged home before symptoms develop. Over the first few weeks of life, most infants with laryngomalacia will develop a characteristic high-pitched inspiratory stridor. The sound can be alarming to parents and others, but in most cases infants are otherwise happy and developing well. Symptoms may become exacerbated when the baby lays on its back and/or during feeding. The cry is invariably normal and sleep is usually uneventful.

Cases of laryngomalacia fall into the “moderate” category when there are feeding and weight gain issues and sleep disruption. In these cases, laryngeal sensation may be blunted, leading to a discoordination of the suck-swallow-breath mechanics. Due to the coexistence of gastroesophageal reflux and laryngomalacia, these symptomatic patients should be managed with anti-reflux therapy and closely monitored.

About 5% of infants with laryngomalacia will fall into the severe range with failure to thrive, obstructive sleep apnea, and/or signs of respiratory distress including tachypnea and retractions. These children require supraglottoplasty surgery to relieve the obstruction.

As a rule of thumb, all patients with suspected laryngomalacia should be evaluated by a pediatric otolaryngologist. In most cases, we perform in-office flexible laryngoscopy to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other pathology, including cysts or neurologic conditions. Patients with more severe presentations (failure to thrive, retractions, aspiration, comorbidities) may be best served by an evaluation in CHOP’s Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders, staffed by airway surgeons and NPs, Pulmonology, Gastroenterology, and Speech Therapy.

The center’s multidisciplinary approach is ideal for complex airway issues such as E.S.’s, subglottic or tracheal stenosis, and laryngeal clefts. The center is a world-renowned program dedicated to diagnosis and treatment of aerodigestive issues. Our experts in the field of neonatal and pediatric airway disorders incorporate innovative treatments and perform state-of-the-art airway reconstructive procedures. Our airway surgeons are experts in laryngotracheal reconstruction, slide tracheoplasty, laryngeal cleft repair, partial cricotracheal resection, and creating a patient-specific recovery plan. Coordinated and comprehensive care stems from the ability to have all 3 services see the child and family in one room and perform triple endoscopies in the operating room under one anesthesia. Our breakthrough research is to improve the lives and care for the aerodigestive child.

Referral information

To make a referral to the Division of Otolaryngology and our specialty programs, call 215-590-3440. Information on all our programs can be found at chop.edu/ent.

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

Case

E.S., a 23-day-old female, was referred to our Pediatric Otolaryngology service for evaluation of noisy breathing. Her pediatrician, Kristen Danley, MD, reported intermittent inspiratory stridor was noted in the first 2 weeks after birth. Due to concerns for choking and gasping with feeds that could suggest a more significant laryngomalacia, E.S. was referred for an otolaryngology evaluation.

E.S.’s parents reported a history of an intermittent “high pitched” sound on inspiration beginning shortly after birth, worse when feeding and sleeping. History was negative for voice concerns, cyanosis or obstructive pauses during sleep. Occasional spitting up was noted after feeds. E.S. was born at term by vaginal delivery to a healthy G1P1 mother. Her birth was uneventful with Apgar scores of 8 and 9. Her birth weight was 3.5 kg (69%ile). On exam, E.S. was well-appearing, alert, and in no distress. High-pitched inspiratory stridor was noted without retractions. Flexible laryngoscopy demonstrated short aryepiglottic folds with redundant soft-tissue hooding over the vocal folds, consistent with laryngomalacia. We advocated a conservative “wait and see” approach.

One month following her initial visit, Danley called, concerned that E.S. was not growing, was tachypneic with feeds, stridulous, and had moderate retractions at rest. E.S. came weekly for weight checks, and besides other symptoms, Danley noted that E.S. fatigued easily with feedings, not taking greater than 2 oz at a time. Danley switched Ella from breast to bottle, initiated Ranitidine, and referred her to Gastroenterology.

On Otolaryngology follow-up, E.S. was noted to have increased stridor and work of breathing. Her weight was 4.1 kg (1%ile). (See Figure 3.) After discussion with Danley and the family, the shared decision was made to admit Ella to CHOP for nasogastric tube feeding and proceed with supraglottoplasty to surgically correct her laryngomalacia. Surgery was performed without complication, and E.S.’s symptoms resolved over the next 2 days. She was discharged on post-op day 3 and the NG tube removed shortly thereafter. At 1 month follow-up, she was asymptomatic and her weight had increased to 5.2 kg (5%ile).

Discussion

Laryngomalacia is by far the most common diagnosis made in infants with noisy breathing. It is estimated that 60% of infant stridor is attributable to laryngomalacia, although that number is probably an underestimate given that many patients are probably not referred for evaluation of mild symptoms. Most patients with laryngomalacia are born without complication and are discharged home before symptoms develop. Over the first few weeks of life, most infants with laryngomalacia will develop a characteristic high-pitched inspiratory stridor. The sound can be alarming to parents and others, but in most cases infants are otherwise happy and developing well. Symptoms may become exacerbated when the baby lays on its back and/or during feeding. The cry is invariably normal and sleep is usually uneventful.

Cases of laryngomalacia fall into the “moderate” category when there are feeding and weight gain issues and sleep disruption. In these cases, laryngeal sensation may be blunted, leading to a discoordination of the suck-swallow-breath mechanics. Due to the coexistence of gastroesophageal reflux and laryngomalacia, these symptomatic patients should be managed with anti-reflux therapy and closely monitored.

About 5% of infants with laryngomalacia will fall into the severe range with failure to thrive, obstructive sleep apnea, and/or signs of respiratory distress including tachypnea and retractions. These children require supraglottoplasty surgery to relieve the obstruction.

As a rule of thumb, all patients with suspected laryngomalacia should be evaluated by a pediatric otolaryngologist. In most cases, we perform in-office flexible laryngoscopy to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other pathology, including cysts or neurologic conditions. Patients with more severe presentations (failure to thrive, retractions, aspiration, comorbidities) may be best served by an evaluation in CHOP’s Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders, staffed by airway surgeons and NPs, Pulmonology, Gastroenterology, and Speech Therapy.

The center’s multidisciplinary approach is ideal for complex airway issues such as E.S.’s, subglottic or tracheal stenosis, and laryngeal clefts. The center is a world-renowned program dedicated to diagnosis and treatment of aerodigestive issues. Our experts in the field of neonatal and pediatric airway disorders incorporate innovative treatments and perform state-of-the-art airway reconstructive procedures. Our airway surgeons are experts in laryngotracheal reconstruction, slide tracheoplasty, laryngeal cleft repair, partial cricotracheal resection, and creating a patient-specific recovery plan. Coordinated and comprehensive care stems from the ability to have all 3 services see the child and family in one room and perform triple endoscopies in the operating room under one anesthesia. Our breakthrough research is to improve the lives and care for the aerodigestive child.

Referral information

To make a referral to the Division of Otolaryngology and our specialty programs, call 215-590-3440. Information on all our programs can be found at chop.edu/ent.

Contact us

Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders