Case:

KD is a 14-year-old female with no prior medical history who presents to your outpatient office with a 6-month history of generalized abdominal pain that has been increasing in frequency over time. The pain is crampy in nature and does not radiate. She also has between 2 to 4 loose and non-bloody stools daily, which is a change from her baseline stool characteristics. Her pain does not typically improve after defecation. Her appetite is inconsistent and she has intermittent nausea. The symptoms seemed to coincide with the start of the current school year, her freshman year of high school. She has been taking lactobacillus every day for the past month without any change in symptoms. Although her sleep has been affected periodically by pain and bowel movements, she continues to do very well academically and has not missed class due to symptoms. She lives with her mother and spends weekends with her father, as they separated 8 months ago.

She does not have any tenderness on exam or organomegaly. Her perianal and rectal examination is unremarkable. Growth parameters show no weight gain from her well child exam 2 years prior, but an appropriate increase in height. She has a slight unspecified anemia. Stool studies for common enteric pathogens were negative.

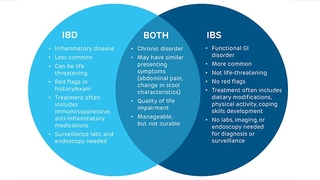

Discussion: While the presentation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may be very similar, there are clinical clues and diagnostic tools that can help make the crucial distinction between these two conditions.

IBD, which includes Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, are chronic inflammatory conditions of the digestive track. The proposed pathophysiology is complex, involving interplay between gut flora, environmental factors, an altered mucosal immune system, and genetic factors. The incidence of IBD continues to increase in children, and particularly so in young, school-aged children.

The presentation of these conditions includes a broad range of extra-intestinal and constitutional symptoms. While abdominal pain, loose stools, and loss of appetite are non-specific, fecal urgency and hematochezia may indicate colitis, whereas growth delay may indicate small bowel disease. Vomiting in this context could reflect bowel stricturing. Unexplained fevers, chronic rashes (erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangranosum), arthritis/enthesitis, and ocular symptoms may also be present. Physical exam may reveal clues like oral ulceration, perianal fistulae, and skin tags, in addition to the extra-intestinal manifestations.

Initial testing should include ruling out infection and assessing inflammatory markers (serum and stool), screening for anemia, hypoalbuminemia, electrolytes, and liver enzymes. Definitive diagnosis requires endoscopic evaluation and possibly abdominal imaging. Once a diagnosis is confirmed, treatment is dependent on the disease phenotype, severity, and several other factors. There are several classes of biologics, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory medications which are used as maintenance therapy. The primary goal is to achieve a brisk and deep remission, which will substantially decrease the risk for disease relapse and long-term complications.

Features of IBS

IBS may also present with abdominal pain and altered bowel movements, but without evidence of another medical condition. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, sensation of incomplete evacuation, and straining. Classification of IBS is based on the Rome criteria, which differentiates subtypes. These include: IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhea, IBS with mixed bowel habits, and IBS unclassified. In these classifications, patients must have recurrent abdominal pain for more than 1 day a week and more than 3 months along with a change in bowel patterns.

The etiology of IBS is likely multifactorial including alterations in GI motility, visceral hypersensitivity, dysbiosis, food sensitivity, and genetic predisposition. There is evidence that underlying psychological distress, including neonatal stress, may be a trigger for development of IBS.

Medical work up for IBS is not typically necessary if there are no concerning signs, which include unintentional weight loss, growth delay, significant vomiting or diarrhea, GI bleeding, fevers, or abnormalities on physical exam.

Treatment options for IBS vary and include cognitive behavioral therapy, diet, and medical therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to improve symptoms in patients with IBS compared with medication alone. Dietary options include increasing fiber, lactose-free diet, and a low-FODMAP (fermentable oligosacchardiases, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) diet. Medical therapy is dependent on the subtype of IBS and can include peppermint oil, antispasmodic medications, and tricyclic antidepressants for pain-predominant IBS; loperamide, cholestyramine, and rifaximin for diarrhea-predominant IBS; and laxatives or secretagogues (lubriprostone, linaclotide, placanatide) for constipation-predominant IBS. The overall goal of treatment is to decrease symptoms and return to normal function.

Diagnosis Is IBD

The 14-year-old girl above was ultimately diagnosed with IBD, specifically Crohn disease. Although there are some psychosocial stressors in this case, which may sway the reader toward IBS, her persistent loose stools, growth deceleration, anemia, nocturnal pain, and stooling are key red flag symptoms that should raise suspicion for IBD and trigger further evaluation.

Initial evaluation for patients with chronic abdominal pain should include a thorough history with a focus on red-flag symptoms. For red-flag symptoms or lab abnormalities, referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist is the next step to confirm diagnosis with endoscopy and colonoscopy. In patients with symptoms consistent with IBS, referral to pediatric gastroenterology is also integral for treatment and multidisciplinary care.

The CHOP Center for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease is one of the largest of its kind in the United States and a leader in research and quality improvement. The team includes a core group of gastroenterologists, as well as clinical psychologists, dietitians, nurse care coordinators, and a social worker. Within the center is a program dedicated to very early onset (VEO) IBD, for children diagnosed before the age of 5, which features an interdisciplinary group of gastroenterologist, immunologists, and geneticists.

The Lustgarten Motility Center in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition focuses on a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach to patients with IBS. Patients with IBS are seen by individual pediatric gastroenterology providers and can also be seen in our interdisciplinary clinic, which includes a gastroenterologist, dietitian, psychologist, and social worker. The aim of the clinic is to improve the quality of life of patients and to streamline care with the team approach.

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

Case:

KD is a 14-year-old female with no prior medical history who presents to your outpatient office with a 6-month history of generalized abdominal pain that has been increasing in frequency over time. The pain is crampy in nature and does not radiate. She also has between 2 to 4 loose and non-bloody stools daily, which is a change from her baseline stool characteristics. Her pain does not typically improve after defecation. Her appetite is inconsistent and she has intermittent nausea. The symptoms seemed to coincide with the start of the current school year, her freshman year of high school. She has been taking lactobacillus every day for the past month without any change in symptoms. Although her sleep has been affected periodically by pain and bowel movements, she continues to do very well academically and has not missed class due to symptoms. She lives with her mother and spends weekends with her father, as they separated 8 months ago.

She does not have any tenderness on exam or organomegaly. Her perianal and rectal examination is unremarkable. Growth parameters show no weight gain from her well child exam 2 years prior, but an appropriate increase in height. She has a slight unspecified anemia. Stool studies for common enteric pathogens were negative.

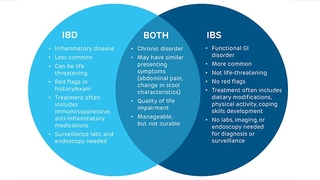

Discussion: While the presentation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may be very similar, there are clinical clues and diagnostic tools that can help make the crucial distinction between these two conditions.

IBD, which includes Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, are chronic inflammatory conditions of the digestive track. The proposed pathophysiology is complex, involving interplay between gut flora, environmental factors, an altered mucosal immune system, and genetic factors. The incidence of IBD continues to increase in children, and particularly so in young, school-aged children.

The presentation of these conditions includes a broad range of extra-intestinal and constitutional symptoms. While abdominal pain, loose stools, and loss of appetite are non-specific, fecal urgency and hematochezia may indicate colitis, whereas growth delay may indicate small bowel disease. Vomiting in this context could reflect bowel stricturing. Unexplained fevers, chronic rashes (erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangranosum), arthritis/enthesitis, and ocular symptoms may also be present. Physical exam may reveal clues like oral ulceration, perianal fistulae, and skin tags, in addition to the extra-intestinal manifestations.

Initial testing should include ruling out infection and assessing inflammatory markers (serum and stool), screening for anemia, hypoalbuminemia, electrolytes, and liver enzymes. Definitive diagnosis requires endoscopic evaluation and possibly abdominal imaging. Once a diagnosis is confirmed, treatment is dependent on the disease phenotype, severity, and several other factors. There are several classes of biologics, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory medications which are used as maintenance therapy. The primary goal is to achieve a brisk and deep remission, which will substantially decrease the risk for disease relapse and long-term complications.

Features of IBS

IBS may also present with abdominal pain and altered bowel movements, but without evidence of another medical condition. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, sensation of incomplete evacuation, and straining. Classification of IBS is based on the Rome criteria, which differentiates subtypes. These include: IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhea, IBS with mixed bowel habits, and IBS unclassified. In these classifications, patients must have recurrent abdominal pain for more than 1 day a week and more than 3 months along with a change in bowel patterns.

The etiology of IBS is likely multifactorial including alterations in GI motility, visceral hypersensitivity, dysbiosis, food sensitivity, and genetic predisposition. There is evidence that underlying psychological distress, including neonatal stress, may be a trigger for development of IBS.

Medical work up for IBS is not typically necessary if there are no concerning signs, which include unintentional weight loss, growth delay, significant vomiting or diarrhea, GI bleeding, fevers, or abnormalities on physical exam.

Treatment options for IBS vary and include cognitive behavioral therapy, diet, and medical therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to improve symptoms in patients with IBS compared with medication alone. Dietary options include increasing fiber, lactose-free diet, and a low-FODMAP (fermentable oligosacchardiases, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) diet. Medical therapy is dependent on the subtype of IBS and can include peppermint oil, antispasmodic medications, and tricyclic antidepressants for pain-predominant IBS; loperamide, cholestyramine, and rifaximin for diarrhea-predominant IBS; and laxatives or secretagogues (lubriprostone, linaclotide, placanatide) for constipation-predominant IBS. The overall goal of treatment is to decrease symptoms and return to normal function.

Diagnosis Is IBD

The 14-year-old girl above was ultimately diagnosed with IBD, specifically Crohn disease. Although there are some psychosocial stressors in this case, which may sway the reader toward IBS, her persistent loose stools, growth deceleration, anemia, nocturnal pain, and stooling are key red flag symptoms that should raise suspicion for IBD and trigger further evaluation.

Initial evaluation for patients with chronic abdominal pain should include a thorough history with a focus on red-flag symptoms. For red-flag symptoms or lab abnormalities, referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist is the next step to confirm diagnosis with endoscopy and colonoscopy. In patients with symptoms consistent with IBS, referral to pediatric gastroenterology is also integral for treatment and multidisciplinary care.

The CHOP Center for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease is one of the largest of its kind in the United States and a leader in research and quality improvement. The team includes a core group of gastroenterologists, as well as clinical psychologists, dietitians, nurse care coordinators, and a social worker. Within the center is a program dedicated to very early onset (VEO) IBD, for children diagnosed before the age of 5, which features an interdisciplinary group of gastroenterologist, immunologists, and geneticists.

The Lustgarten Motility Center in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition focuses on a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach to patients with IBS. Patients with IBS are seen by individual pediatric gastroenterology providers and can also be seen in our interdisciplinary clinic, which includes a gastroenterologist, dietitian, psychologist, and social worker. The aim of the clinic is to improve the quality of life of patients and to streamline care with the team approach.

Contact us

Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition