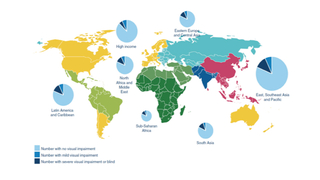

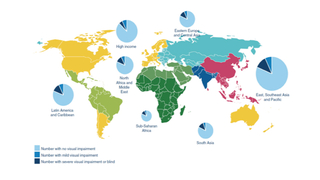

The risk of blindness due to retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) varies dramatically depending on the level of neonatal and ophthalmologic care given in neonatal intensive care units and a country’s socioeconomic development. As recently as 2010, an estimated 33,000 premature infants became blind or visually impaired from ROP each year worldwide (see map). In regions with high levels of neonatal care and adequate resources, ROP blindness is largely restricted to extremely premature infants with very low birth weight and low gestational age.

However, in middle- and low-income countries including Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia with rapidly developing neonatal intensive care systems and limited health resources to care for the premature newborn, blindness due to ROP has recently emerged as an increasing problem in bigger, more mature infants as well. Common reasons why infants in these countries become blind from ROP include:

- The unit in which they are treated lacks services for the detection and/or treatment of ROP

- The infant exceeds birth weight criteria for examination and hence is not screened for ROP

- The examination and treatment aren’t carried out effectively

- The baby is exposed to excess oxygen due to lack of or poor oxygen saturation measuring techniques

For more than 20 years, Graham Quinn, MD, MSCE, Attending Surgeon in the Division of Pediatric Ophthalmology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania, has worked with a group of ROP experts to help clinicians caring for preemies in developing countries establish comprehensive ROP screening and treatment programs. He served as a member of the original group that developed the International Classification of ROP and recently chaired a “revisiting” of the classification, and has been involved in convening three World Congresses on ROP blindness since the early 2000s.

When invited by neonatologists and ophthalmologists in various regions of the world with rapidly developing neonatal care, Quinn and his colleagues convene two- to three-day workshops for neonatologists, ophthalmologists, nurses and other stakeholders. The goals of these collaborative workshops are to:

- Get an understanding of the current ROP situation in each country

- Develop or improve national screening guidelines

- Institute the use of standardized forms for ROP and neonatal data

- Establish short- and long-term goals for ROP blindness prevention

Given that bigger, more mature infants are becoming blind from ROP in these countries, the team stresses developing screening criteria based on local data from the population of premature infants being cared for in that particular country. In the absence of data, wide criteria are used for birth weight and gestational age in an effort to capture all babies with ROP.

Empowering local teams to treat ROP blindness

The workshops are designed to raise awareness of ROP blindness and to transfer skills and resources to local teams so they can provide long-term care for the children in their communities. Neonatologists, ophthalmologists and nurses are instructed on how to carefully monitor risk factors, including oxygen administration, and an emphasis is placed on making improvements to equipment and personnel.

Quinn and colleagues return a year or two after the workshop to evaluate what worked and what didn’t work, and develop plans with the local clinicians on where to go from there.

“What I like about it is I am not going and taking care of their kids,” says Quinn. “I am going there and helping physicians, nurses and the country’s Ministry of Health develop skills so that they can take care of their kids.”

This approach has proven effective in Latin America over the last 15 years. For example, at a Latin American workshop held in Lima, Peru in 2005, five countries of the 19 in attendance didn’t have an ROP screening program. Since that time, with the extensive effort and support of Quinn and his colleagues, all five countries have developed programs and others have improved their programs.

“I am grateful and privileged to contribute to the prevention of ROP blindness, which has become an epidemic as neonatal care services expand to new regions leading to increased survival of premature infants,” says Quinn. “I enjoy the one-on-one care that I can deliver at CHOP, and also the one-to-many care that we provide in this international work.”

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

The risk of blindness due to retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) varies dramatically depending on the level of neonatal and ophthalmologic care given in neonatal intensive care units and a country’s socioeconomic development. As recently as 2010, an estimated 33,000 premature infants became blind or visually impaired from ROP each year worldwide (see map). In regions with high levels of neonatal care and adequate resources, ROP blindness is largely restricted to extremely premature infants with very low birth weight and low gestational age.

However, in middle- and low-income countries including Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia with rapidly developing neonatal intensive care systems and limited health resources to care for the premature newborn, blindness due to ROP has recently emerged as an increasing problem in bigger, more mature infants as well. Common reasons why infants in these countries become blind from ROP include:

- The unit in which they are treated lacks services for the detection and/or treatment of ROP

- The infant exceeds birth weight criteria for examination and hence is not screened for ROP

- The examination and treatment aren’t carried out effectively

- The baby is exposed to excess oxygen due to lack of or poor oxygen saturation measuring techniques

For more than 20 years, Graham Quinn, MD, MSCE, Attending Surgeon in the Division of Pediatric Ophthalmology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania, has worked with a group of ROP experts to help clinicians caring for preemies in developing countries establish comprehensive ROP screening and treatment programs. He served as a member of the original group that developed the International Classification of ROP and recently chaired a “revisiting” of the classification, and has been involved in convening three World Congresses on ROP blindness since the early 2000s.

When invited by neonatologists and ophthalmologists in various regions of the world with rapidly developing neonatal care, Quinn and his colleagues convene two- to three-day workshops for neonatologists, ophthalmologists, nurses and other stakeholders. The goals of these collaborative workshops are to:

- Get an understanding of the current ROP situation in each country

- Develop or improve national screening guidelines

- Institute the use of standardized forms for ROP and neonatal data

- Establish short- and long-term goals for ROP blindness prevention

Given that bigger, more mature infants are becoming blind from ROP in these countries, the team stresses developing screening criteria based on local data from the population of premature infants being cared for in that particular country. In the absence of data, wide criteria are used for birth weight and gestational age in an effort to capture all babies with ROP.

Empowering local teams to treat ROP blindness

The workshops are designed to raise awareness of ROP blindness and to transfer skills and resources to local teams so they can provide long-term care for the children in their communities. Neonatologists, ophthalmologists and nurses are instructed on how to carefully monitor risk factors, including oxygen administration, and an emphasis is placed on making improvements to equipment and personnel.

Quinn and colleagues return a year or two after the workshop to evaluate what worked and what didn’t work, and develop plans with the local clinicians on where to go from there.

“What I like about it is I am not going and taking care of their kids,” says Quinn. “I am going there and helping physicians, nurses and the country’s Ministry of Health develop skills so that they can take care of their kids.”

This approach has proven effective in Latin America over the last 15 years. For example, at a Latin American workshop held in Lima, Peru in 2005, five countries of the 19 in attendance didn’t have an ROP screening program. Since that time, with the extensive effort and support of Quinn and his colleagues, all five countries have developed programs and others have improved their programs.

“I am grateful and privileged to contribute to the prevention of ROP blindness, which has become an epidemic as neonatal care services expand to new regions leading to increased survival of premature infants,” says Quinn. “I enjoy the one-on-one care that I can deliver at CHOP, and also the one-to-many care that we provide in this international work.”

Contact us

Division of Ophthalmology