Case: AB is an 11-year-old girl who presents to the emergency department, with her father, with a concern for constipation and abdominal pain. She states that she has had a history of constipation since birth and was prescribed MiraLAX® by her pediatrician in the past, although she had stopped taking it a few weeks ago. She is premenarchal. She describes her stools as intermittently hard, with some straining to evacuate; her last bowel movement just prior to coming to the ED was somewhat loose. She has had some lower abdominal pain recently, which is relieved by acetaminophen. She has not had any fevers or vomiting, and her appetite has otherwise been good.

On examination, AB is alert and well appearing. She is well developed and well nourished, and her vital signs are unremarkable. Her abdomen is soft with mild tenderness to palpation in the lower quadrants bilaterally and some suprapubic fullness; there is no rebound or guarding. Her neurologic examination is unremarkable, and there are no unusual skin rashes. On rectal examination, there is an empty rectal vault and a soft palpable mass anteriorly.

Discussion

Constipation is a common pediatric problem estimated to affect around 30% of children and accounts for a significant number of primary care and emergency department visits annually. Abdominal pain is the most frequent primary complaint, but other symptoms include painful bowel movements, infrequent stooling, bloody stools, urinary complaints, nausea, and encopresis. While the vast majority can be classified as “functional constipation” and treated with dietary/lifestyle modifications and occasionally medications, complications do rarely occur that necessitate more urgent treatments and potential hospital admission for a cleanout or even operative intervention.

As clinicians, there are certain historical pieces of information and exam findings that should raise a red flag for a more insidious process such as obstruction, tumors, or medical conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease or Hirschsprung’s disease, and one should always be on the lookout for these despite the mantra that “common things are common.”

In this 11 yo premenarchal girl, the history of constipation with a cessation of medications certainly points to functional constipation as a leading diagnosis. The prior use of enemas at home without relief is certainly a little unusual, however, and the presence of a palpable mass on rectal examination definitely raises concern for a pathological cause.

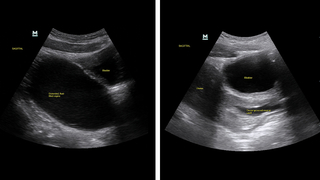

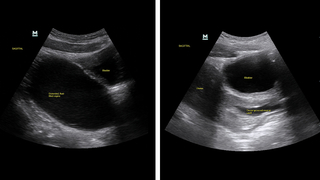

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, a point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) program was established in the early to mid-2010s with a variety of procedural applications as well as diagnostic applications (see Chart 1). In this particular child, a POCUS exam was performed to evaluate for the possibility of urinary retention and constipation. This bedside ultrasound surprisingly showed a minimally distended bladder with an unexpected large fluid-filled structure posterior to the bladder (see Figure 1). These findings raised the concern for hematometrocolpos. Subsequently an external vaginal exam was performed, which showed a bulging bluish mass at the vaginal introitus, consistent with an imperforate hymen. When asked, the patient could not say how long that it had been present and had never mentioned it to her parents.

POCUS

Point-of-care ultrasound has been defined as “the acquisition, interpretation, and immediate clinical integration of ultrasonographic imaging performed by a treating clinician at the patient’s bedside rather than by a radiologist or cardiologist. POCUS is an inclusive term; it is not limited to any specialty, protocol, or organ system. With the advent of smaller and more affordable ultrasound machines, combined with evidence that nonradiologists and noncardiologists can become competent in the performance of POCUS, it is now used in many practice settings and in all phases of care—from screening and diagnosis to procedural guidance and monitoring—and has become associated with changes in clinical decision making in medical practice.” (NEJM reference below) While it is now well established in general emergency medicine and a core competency required for graduation from EM residency, it has only in the past decade or so gained traction in Pediatrics and Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

CHOP is well positioned as a leader in pediatric POCUS. Thanks to close collaboration with experts in Radiology and Cardiology, there are now established programs in the ED, NICU, PICU, Anesthesia, Sports Medicine, and inpatient General Pediatrics/Hospitalist departments—both at our Philadelphia campus and at the Middleman Family Pavilion, CHOP’s new hospital in King of Prussia.

In addition to offering a CHOP-led semiannual POCUS course (chop.edu/cme) that is open to participants from all over the world and caters to multiple specialties, there is ongoing active research and innovative programs that include a Center for Pediatric Contrast Ultrasound. Recently, POCUS has been incorporated into CHOP’s General Pediatrics residency training program, one of the first of its kind, with the goal that all graduating residents will have basic POCUS training and opportunities for more advanced training if desired.

Point-of-care ultrasound

Procedural applications

- vascular access

- nerve blocks

- foreign body removal

- abscess incision and drainage

- spinal taps

Diagnostic applications

- skin and soft tissue infections

- foreign bodies

- cardiac ultrasound for fl uid and function checks

- lung ultrasound for evaluation of pneumothoraces and pneumonia

- bladder assessment for urinary retention and volume assessment

- FAST exam for trauma

- ocular assessment for optic nerve swelling and ocular pathology

- musculoskeletal assessment for fractures and joint effusions

Case resolution

For this patient, general surgery was consulted from the ED and a cruciate hymenectomy was performed under ketamine sedation with immediate return under pressure of approximately 150 cc of old blood; no internal vaginal septa were noted after speculum insertion. A POCUS performed immediately after showed a decompressed vaginal vault (see Figure 2), and she was able to be discharged with close PCP and general surgery follow-up.

For more information, please visit our website.

(Left) Point-of-care ultrasound using a curvilinear probe in sagittal orientation shows a large fluid-filled structure posterior to the bladder and extending superiorly. (Right) Point-of-care ultrasound in sagittal orientation after hymenectomy showing a decompressed vaginal vault posterior to the bladder; the uterus can now be seen superiorly and is also decompressed.

Reference and further reading

Diaz-Gomez J, Mayo P, Koenig S. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1593-602.

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

Case: AB is an 11-year-old girl who presents to the emergency department, with her father, with a concern for constipation and abdominal pain. She states that she has had a history of constipation since birth and was prescribed MiraLAX® by her pediatrician in the past, although she had stopped taking it a few weeks ago. She is premenarchal. She describes her stools as intermittently hard, with some straining to evacuate; her last bowel movement just prior to coming to the ED was somewhat loose. She has had some lower abdominal pain recently, which is relieved by acetaminophen. She has not had any fevers or vomiting, and her appetite has otherwise been good.

On examination, AB is alert and well appearing. She is well developed and well nourished, and her vital signs are unremarkable. Her abdomen is soft with mild tenderness to palpation in the lower quadrants bilaterally and some suprapubic fullness; there is no rebound or guarding. Her neurologic examination is unremarkable, and there are no unusual skin rashes. On rectal examination, there is an empty rectal vault and a soft palpable mass anteriorly.

Discussion

Constipation is a common pediatric problem estimated to affect around 30% of children and accounts for a significant number of primary care and emergency department visits annually. Abdominal pain is the most frequent primary complaint, but other symptoms include painful bowel movements, infrequent stooling, bloody stools, urinary complaints, nausea, and encopresis. While the vast majority can be classified as “functional constipation” and treated with dietary/lifestyle modifications and occasionally medications, complications do rarely occur that necessitate more urgent treatments and potential hospital admission for a cleanout or even operative intervention.

As clinicians, there are certain historical pieces of information and exam findings that should raise a red flag for a more insidious process such as obstruction, tumors, or medical conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease or Hirschsprung’s disease, and one should always be on the lookout for these despite the mantra that “common things are common.”

In this 11 yo premenarchal girl, the history of constipation with a cessation of medications certainly points to functional constipation as a leading diagnosis. The prior use of enemas at home without relief is certainly a little unusual, however, and the presence of a palpable mass on rectal examination definitely raises concern for a pathological cause.

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, a point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) program was established in the early to mid-2010s with a variety of procedural applications as well as diagnostic applications (see Chart 1). In this particular child, a POCUS exam was performed to evaluate for the possibility of urinary retention and constipation. This bedside ultrasound surprisingly showed a minimally distended bladder with an unexpected large fluid-filled structure posterior to the bladder (see Figure 1). These findings raised the concern for hematometrocolpos. Subsequently an external vaginal exam was performed, which showed a bulging bluish mass at the vaginal introitus, consistent with an imperforate hymen. When asked, the patient could not say how long that it had been present and had never mentioned it to her parents.

POCUS

Point-of-care ultrasound has been defined as “the acquisition, interpretation, and immediate clinical integration of ultrasonographic imaging performed by a treating clinician at the patient’s bedside rather than by a radiologist or cardiologist. POCUS is an inclusive term; it is not limited to any specialty, protocol, or organ system. With the advent of smaller and more affordable ultrasound machines, combined with evidence that nonradiologists and noncardiologists can become competent in the performance of POCUS, it is now used in many practice settings and in all phases of care—from screening and diagnosis to procedural guidance and monitoring—and has become associated with changes in clinical decision making in medical practice.” (NEJM reference below) While it is now well established in general emergency medicine and a core competency required for graduation from EM residency, it has only in the past decade or so gained traction in Pediatrics and Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

CHOP is well positioned as a leader in pediatric POCUS. Thanks to close collaboration with experts in Radiology and Cardiology, there are now established programs in the ED, NICU, PICU, Anesthesia, Sports Medicine, and inpatient General Pediatrics/Hospitalist departments—both at our Philadelphia campus and at the Middleman Family Pavilion, CHOP’s new hospital in King of Prussia.

In addition to offering a CHOP-led semiannual POCUS course (chop.edu/cme) that is open to participants from all over the world and caters to multiple specialties, there is ongoing active research and innovative programs that include a Center for Pediatric Contrast Ultrasound. Recently, POCUS has been incorporated into CHOP’s General Pediatrics residency training program, one of the first of its kind, with the goal that all graduating residents will have basic POCUS training and opportunities for more advanced training if desired.

Point-of-care ultrasound

Procedural applications

- vascular access

- nerve blocks

- foreign body removal

- abscess incision and drainage

- spinal taps

Diagnostic applications

- skin and soft tissue infections

- foreign bodies

- cardiac ultrasound for fl uid and function checks

- lung ultrasound for evaluation of pneumothoraces and pneumonia

- bladder assessment for urinary retention and volume assessment

- FAST exam for trauma

- ocular assessment for optic nerve swelling and ocular pathology

- musculoskeletal assessment for fractures and joint effusions

Case resolution

For this patient, general surgery was consulted from the ED and a cruciate hymenectomy was performed under ketamine sedation with immediate return under pressure of approximately 150 cc of old blood; no internal vaginal septa were noted after speculum insertion. A POCUS performed immediately after showed a decompressed vaginal vault (see Figure 2), and she was able to be discharged with close PCP and general surgery follow-up.

For more information, please visit our website.

(Left) Point-of-care ultrasound using a curvilinear probe in sagittal orientation shows a large fluid-filled structure posterior to the bladder and extending superiorly. (Right) Point-of-care ultrasound in sagittal orientation after hymenectomy showing a decompressed vaginal vault posterior to the bladder; the uterus can now be seen superiorly and is also decompressed.

Reference and further reading

Diaz-Gomez J, Mayo P, Koenig S. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1593-602.

Contact us

Emergency Medicine