A 3-year-old girl presents for evaluation of red and irritated left eye of 5 days duration. Past medical history is noteworthy for eczema. She denies any sick contacts or recent upper respiratory infection. Her mother also notes the presence of a rash around her daughter’s left eye. The rash worsened with use of topical steroids medication.

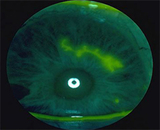

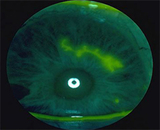

On examination, there were multiple, discrete, and coalescing vesicles on an erythematous base along the left lower lid. The bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva appear inflamed. Fluorescein staining revealed positive corneal staining in a dendritic pattern.

Discussion: The patient is especially at risk for herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) with ocular involvement because of her history of eczema. The worsening of a rash with topical steroid use is suspicious for herpetic dermatitis as well. Dendritic lesions of the cornea can be seen with fluoroscein stain and a cobalt blue light of direct ophthalmoscope. HSV can also cause blepharoconjunctivitis and stromal keratitis.

HSV-1 should be suspected in any pediatric patient with recurrent unilateral keratoconjunctivitis. Children tend to have poorer visual outcomes as compared with adults with HSV because they can be difficult to examine, resistant to topical medications, and are susceptible to amblyopia. Furthermore, children with ocular HSV have a higher rate of misdiagnosis, increasing the risk of corneal scarring and vision loss.

Recurrence of HSV keratitis is more likely to occur in children, with a rate above 50% and a mean time to recurrence of 13 months.

Liu et al. found that in children with herpetic blepharoconjunctivitis (HBC), there appears to be an increased rate of asthma, atopy, and systemic disease. The sensitivity of atopic patients to HSV infection may in part result from depression of Th1-cell activity, which is the primary effective immune response against ocular HSV. Instead, atopic individuals display a predominant Th2-cell response, which suppresses Th1 activity and hinders effective immunity against HSV.

Children with HSV keratitis tend to have poor visual outcomes. Liu et al. most recently reported final vision of 20/40 or worse in 10 of 39 eyes (26%) of their pediatric patients with HSV keratitis. Corneal scars may develop in up to 80% of these patients, with as many as half being centrally located. In addition, patients are at risk for refractive amblyopia caused by keratitis-induced astigmatism. Liu et al. reported more than two diopters of astigmatism in 11 of 39 eyes with herpes simplex keratitis (HSK).

Confirming Diagnosis in the Lab: Whereas most cases of HSV keratitis are diagnosed based on clinical exam, atypical presentations benefit from laboratory confirmation to more rapidly and definitively confirm a diagnosis. The gold standard for detection of HSV-1 is through live viral culture, but this process is time-consuming and carries with it a low sensitivity. Available modalities for detection of HSV include immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). However, both require expensive equipment, special training, and are difficult to perform in the clinical setting. Furthermore, PCR is very sensitive and often detects physiologic HSV shedding in normal individuals. Nonetheless, if a laboratory is readily accessible, PCR remains the gold standard for molecular diagnosis.

A recently developed alternative for fast and efficient detection of HSV is the immunochromatographic assay (ICGA) kit (Checkmate Herpes Eye, Wakamoto Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan). It utilizes a monoclonal antibody against HSV glycoprotein D which is present on the HSV virion and required for infectivity. The kit can be performed as an “in the office” diagnostic test within 15 minutes. Inoue et al. recently explored its efficacy (see References). An ICGA kit will likely not be useful as a general screening tool, but given the high rate of misdiagnosis and atypical presentation of ocular HSV in children, it may be valuable in the pediatric office.

Medical Management: Oral acyclovir (ACV) is an effective treatment of herpetic keratitis. Various groups have shown that oral acyclovir is well tolerated in the pediatric population. As children tend to have difficulty with eyedrop regimens, oral therapy is a desirable treatment option. Furthermore, there are local toxicity issues with topical agents that can be avoided using oral regimens.

Medical Management: Oral Acyclovir

Age/Dosage/Frequency

- Younger than 18 months: 100 mg, 3 times/day

- 18 months to 3 years: 200 mg, 3 times/day

- 3 to 5 years: 300 mg, 3 times/day

- Older than 6 years: 400 mg, 3 times/day

Given the higher rate of recurrence of herpetic keratitis in children, long-term prophylactic oral ACV is frequently employed, especially in stromal disease. Although its use in children is currently off-label, ACV has a wide safety margin, with maximal tolerated daily doses of 40mg to 80mg/kg/day. For prophylactic dosing, follow the same regimen as for treatment, but give 2 times per day instead of 3 times per day administration. Prophylaxis should be extended for at least 1 year after the last episode of recurrence, with periodic kidney and liver function monitoring.

References and Suggested Readings

Liu S, Pavan-Langston D, Colby K. Pediatric herpes simplex of the anterior segment: characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2003–2008.

Inoue Y, Shimomura Y, Fukuda M, et al. Multicentre clinical study of the herpes simplex virus immunochromatographic assay kit for the diagnosis of herpetic epithelial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;00:1–5.

Inoue T, Kawashima R, Suzuki T, Ohashi Y. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for diagnosing acyclovir-resistant herpetic keratitis based on changes in viral DNA copy number before and after treatment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:1462–1464. [This paper details clever use of RT-PCR in management of HSK not responding to therapy.]

Referral information

To refer a patient to CHOP’s Division of Ophthalmology, call 215-590-2791.

A 3-year-old girl presents for evaluation of red and irritated left eye of 5 days duration. Past medical history is noteworthy for eczema. She denies any sick contacts or recent upper respiratory infection. Her mother also notes the presence of a rash around her daughter’s left eye. The rash worsened with use of topical steroids medication.

On examination, there were multiple, discrete, and coalescing vesicles on an erythematous base along the left lower lid. The bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva appear inflamed. Fluorescein staining revealed positive corneal staining in a dendritic pattern.

Discussion: The patient is especially at risk for herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) with ocular involvement because of her history of eczema. The worsening of a rash with topical steroid use is suspicious for herpetic dermatitis as well. Dendritic lesions of the cornea can be seen with fluoroscein stain and a cobalt blue light of direct ophthalmoscope. HSV can also cause blepharoconjunctivitis and stromal keratitis.

HSV-1 should be suspected in any pediatric patient with recurrent unilateral keratoconjunctivitis. Children tend to have poorer visual outcomes as compared with adults with HSV because they can be difficult to examine, resistant to topical medications, and are susceptible to amblyopia. Furthermore, children with ocular HSV have a higher rate of misdiagnosis, increasing the risk of corneal scarring and vision loss.

Recurrence of HSV keratitis is more likely to occur in children, with a rate above 50% and a mean time to recurrence of 13 months.

Liu et al. found that in children with herpetic blepharoconjunctivitis (HBC), there appears to be an increased rate of asthma, atopy, and systemic disease. The sensitivity of atopic patients to HSV infection may in part result from depression of Th1-cell activity, which is the primary effective immune response against ocular HSV. Instead, atopic individuals display a predominant Th2-cell response, which suppresses Th1 activity and hinders effective immunity against HSV.

Children with HSV keratitis tend to have poor visual outcomes. Liu et al. most recently reported final vision of 20/40 or worse in 10 of 39 eyes (26%) of their pediatric patients with HSV keratitis. Corneal scars may develop in up to 80% of these patients, with as many as half being centrally located. In addition, patients are at risk for refractive amblyopia caused by keratitis-induced astigmatism. Liu et al. reported more than two diopters of astigmatism in 11 of 39 eyes with herpes simplex keratitis (HSK).

Confirming Diagnosis in the Lab: Whereas most cases of HSV keratitis are diagnosed based on clinical exam, atypical presentations benefit from laboratory confirmation to more rapidly and definitively confirm a diagnosis. The gold standard for detection of HSV-1 is through live viral culture, but this process is time-consuming and carries with it a low sensitivity. Available modalities for detection of HSV include immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). However, both require expensive equipment, special training, and are difficult to perform in the clinical setting. Furthermore, PCR is very sensitive and often detects physiologic HSV shedding in normal individuals. Nonetheless, if a laboratory is readily accessible, PCR remains the gold standard for molecular diagnosis.

A recently developed alternative for fast and efficient detection of HSV is the immunochromatographic assay (ICGA) kit (Checkmate Herpes Eye, Wakamoto Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan). It utilizes a monoclonal antibody against HSV glycoprotein D which is present on the HSV virion and required for infectivity. The kit can be performed as an “in the office” diagnostic test within 15 minutes. Inoue et al. recently explored its efficacy (see References). An ICGA kit will likely not be useful as a general screening tool, but given the high rate of misdiagnosis and atypical presentation of ocular HSV in children, it may be valuable in the pediatric office.

Medical Management: Oral acyclovir (ACV) is an effective treatment of herpetic keratitis. Various groups have shown that oral acyclovir is well tolerated in the pediatric population. As children tend to have difficulty with eyedrop regimens, oral therapy is a desirable treatment option. Furthermore, there are local toxicity issues with topical agents that can be avoided using oral regimens.

Medical Management: Oral Acyclovir

Age/Dosage/Frequency

- Younger than 18 months: 100 mg, 3 times/day

- 18 months to 3 years: 200 mg, 3 times/day

- 3 to 5 years: 300 mg, 3 times/day

- Older than 6 years: 400 mg, 3 times/day

Given the higher rate of recurrence of herpetic keratitis in children, long-term prophylactic oral ACV is frequently employed, especially in stromal disease. Although its use in children is currently off-label, ACV has a wide safety margin, with maximal tolerated daily doses of 40mg to 80mg/kg/day. For prophylactic dosing, follow the same regimen as for treatment, but give 2 times per day instead of 3 times per day administration. Prophylaxis should be extended for at least 1 year after the last episode of recurrence, with periodic kidney and liver function monitoring.

References and Suggested Readings

Liu S, Pavan-Langston D, Colby K. Pediatric herpes simplex of the anterior segment: characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2003–2008.

Inoue Y, Shimomura Y, Fukuda M, et al. Multicentre clinical study of the herpes simplex virus immunochromatographic assay kit for the diagnosis of herpetic epithelial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;00:1–5.

Inoue T, Kawashima R, Suzuki T, Ohashi Y. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for diagnosing acyclovir-resistant herpetic keratitis based on changes in viral DNA copy number before and after treatment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:1462–1464. [This paper details clever use of RT-PCR in management of HSK not responding to therapy.]

Referral information

To refer a patient to CHOP’s Division of Ophthalmology, call 215-590-2791.