A 12-year-old boy presented to his pediatrician for a 2-month history of cough, postnasal drip, and nasal congestion. His symptoms, initially intermittent, are now persistent and associated with abdominal pain localized to the mid-chest and xiphoid regions. Wheezing was auscultated on physical examination, and he was treated with a bronchodilator. He returned to the office 1 week later with worsening cough, phlegm, nonbloody, nonbilious emesis, and dysphagia for liquids and solids. He described drinking large quantities of fluids to swallow properly and was able to handle his own secretions. He denied oral regurgitation of food, but had unrelenting chest pain. On physical examination, he was nontoxic and afebrile, but was mildly dyspneic with occasional wheezing. Abdominal examination was unremarkable except for tenderness to palpation at the xiphoid area. A chest X-ray was without evidence of pneumonia. He was prescribed an inhaled steroid for asthma and was started on a proton pump inhibitor.

Two weeks later, his dysphagia was not any better, and he now had a foreign body sensation in his mid-chest associated with meals. He was ordered a barium swallow, which showed distal esophageal tapering and spasm. He was referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation.

Discussion

The child was diagnosed with achalasia, a primary esophageal motor disorder that presents as a functional obstruction at the esophagogastric junction. It is characterized by absence of ganglion cells from the myenteric plexus leading to impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and absence of esophageal peristalsis.

Although it is known that the motor abnormalities seen in achalasia are secondary to neuronal degeneration of the myenteric plexus, the exact etiology of the disease remains unknown.

Achalasia is rare, with an estimated incidence of 1 case per 100000 persons. It occurs equally in both sexes, without racial predilection, and across all ages with a peak incidence in the third and fourth decades of life. Fewer than 5% manifest before 15 years of age. Even more rarely, achalasia has been present in the neonatal period.

The most common symptoms on presentation are vomiting and dysphagia. Dysphagia occurs initially with solids, then with liquids as the disease progresses. Patients describe a sensation of food getting caught in the middle to lower chest. Children with achalasia are usually noted to be slow eaters and swallow repeatedly. Vomiting usually starts as food remnants and progresses to severe vomiting with an inability to eat. The regurgitated food usually is not mixed with gastric juice. Weight loss can be severe, and—especially in young children—failure to thrive, aspiration, and recurrent pneumonia dominate the clinical history.

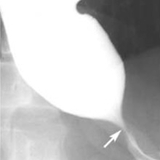

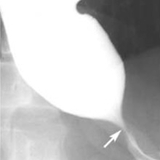

The gold standard for diagnosing achalasia is esophageal manometry; radiographic and endoscopic evaluation provides supplementary information. A chest X-ray may show a widened mediastinum and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. A barium esophagram shows esophageal dilation with tapering at the esophageal junction, known as a “bird beak.” (See Figure 1.) If the esophagus is severely dilated, it can occupy the entire mediastinum, assuming an S curve, known as a sigmoid esophagus. Endoscopy is performed to evaluate for secondary causes of achalasia; it cannot be used for diagnosis as it is often normal.

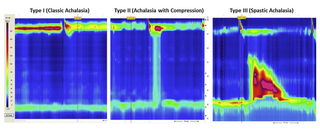

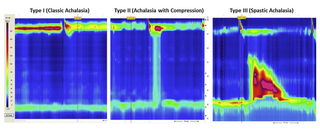

The hallmark findings of achalasia on manometry are absence of esophageal peristalsis and incomplete or partial LES relaxation with wet swallows. Basal LES pressure and intraesophageal pressure may be elevated, but not uniformly. High-resolution esophageal manometry has led to the description of 3 subtypes of achalasia: type I or classic achalasia with low intraesophageal pressure, type II with panesophageal pressurization, and type III with highamplitude spastic contractions. (See Figure 2.) Classification is beneficial as different types have variable responses to similar therapies, with type II having the most favorable response.

Any evaluation should rule out other conditions that may mimic achalasia, including Chagas disease (endemic in South America), or be associated with it, such as triple-A or Allgrove syndrome (adrenocorticotropic hormone insensitivity, alacrima, and achalasia). Patients with anorexia nervosa have been shown to manometrically have achalasia. Achalasia is also more common in patients with Down syndrome.

No treatment can reverse the nerve damage or restore normal esophageal function; however, treatments can relieve symptoms of the functional obstruction. Oral nitrates and calcium channel blockers can relax smooth muscle, resulting in reduced LES pressure and symptomatic relief. Intrasphincteric botulism toxin can be endoscopically injected to reduce LES pressure, but relief usually lasts only 6 months and may affect future surgical intervention. Dilation with pneumatic balloon produces a controlled disruption of the LES fibers. Although there is a high risk of esophageal perforation, pneumatic dilation leads to longer symptomatic improvement. If needed, surgical myotomy to disrupt the LES fibers with or without anti-reflux procedure is the procedure of choice.

Our patient underwent esophageal manometry, which was consistent with type II achalasia. He had an upper endoscopy with pneumatic balloon dilation. Initially, his dysphagia resolved. At the 2-week follow-up, his symptoms began to reappear and he underwent repeat pneumatic dilation with a larger diameter balloon. He has been asymptomatic for the past year. GI continues to follow him as symptoms can recur years after dilation.

References and Suggested Readings

Kahrilas P, Bredenoord A, Fox M, et al. The Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(2):160-174.

Moonen A, Boeckxstaens G. Current diagnosis and management of achalasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(6):484-490.

To refer a patient to the Suzi and Scott Lustgarten Center for GI Motility, call 215-590-1678 or email motilitycenter@email.chop.edu.

A 12-year-old boy presented to his pediatrician for a 2-month history of cough, postnasal drip, and nasal congestion. His symptoms, initially intermittent, are now persistent and associated with abdominal pain localized to the mid-chest and xiphoid regions. Wheezing was auscultated on physical examination, and he was treated with a bronchodilator. He returned to the office 1 week later with worsening cough, phlegm, nonbloody, nonbilious emesis, and dysphagia for liquids and solids. He described drinking large quantities of fluids to swallow properly and was able to handle his own secretions. He denied oral regurgitation of food, but had unrelenting chest pain. On physical examination, he was nontoxic and afebrile, but was mildly dyspneic with occasional wheezing. Abdominal examination was unremarkable except for tenderness to palpation at the xiphoid area. A chest X-ray was without evidence of pneumonia. He was prescribed an inhaled steroid for asthma and was started on a proton pump inhibitor.

Two weeks later, his dysphagia was not any better, and he now had a foreign body sensation in his mid-chest associated with meals. He was ordered a barium swallow, which showed distal esophageal tapering and spasm. He was referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation.

Discussion

The child was diagnosed with achalasia, a primary esophageal motor disorder that presents as a functional obstruction at the esophagogastric junction. It is characterized by absence of ganglion cells from the myenteric plexus leading to impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and absence of esophageal peristalsis.

Although it is known that the motor abnormalities seen in achalasia are secondary to neuronal degeneration of the myenteric plexus, the exact etiology of the disease remains unknown.

Achalasia is rare, with an estimated incidence of 1 case per 100000 persons. It occurs equally in both sexes, without racial predilection, and across all ages with a peak incidence in the third and fourth decades of life. Fewer than 5% manifest before 15 years of age. Even more rarely, achalasia has been present in the neonatal period.

The most common symptoms on presentation are vomiting and dysphagia. Dysphagia occurs initially with solids, then with liquids as the disease progresses. Patients describe a sensation of food getting caught in the middle to lower chest. Children with achalasia are usually noted to be slow eaters and swallow repeatedly. Vomiting usually starts as food remnants and progresses to severe vomiting with an inability to eat. The regurgitated food usually is not mixed with gastric juice. Weight loss can be severe, and—especially in young children—failure to thrive, aspiration, and recurrent pneumonia dominate the clinical history.

The gold standard for diagnosing achalasia is esophageal manometry; radiographic and endoscopic evaluation provides supplementary information. A chest X-ray may show a widened mediastinum and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. A barium esophagram shows esophageal dilation with tapering at the esophageal junction, known as a “bird beak.” (See Figure 1.) If the esophagus is severely dilated, it can occupy the entire mediastinum, assuming an S curve, known as a sigmoid esophagus. Endoscopy is performed to evaluate for secondary causes of achalasia; it cannot be used for diagnosis as it is often normal.

The hallmark findings of achalasia on manometry are absence of esophageal peristalsis and incomplete or partial LES relaxation with wet swallows. Basal LES pressure and intraesophageal pressure may be elevated, but not uniformly. High-resolution esophageal manometry has led to the description of 3 subtypes of achalasia: type I or classic achalasia with low intraesophageal pressure, type II with panesophageal pressurization, and type III with highamplitude spastic contractions. (See Figure 2.) Classification is beneficial as different types have variable responses to similar therapies, with type II having the most favorable response.

Any evaluation should rule out other conditions that may mimic achalasia, including Chagas disease (endemic in South America), or be associated with it, such as triple-A or Allgrove syndrome (adrenocorticotropic hormone insensitivity, alacrima, and achalasia). Patients with anorexia nervosa have been shown to manometrically have achalasia. Achalasia is also more common in patients with Down syndrome.

No treatment can reverse the nerve damage or restore normal esophageal function; however, treatments can relieve symptoms of the functional obstruction. Oral nitrates and calcium channel blockers can relax smooth muscle, resulting in reduced LES pressure and symptomatic relief. Intrasphincteric botulism toxin can be endoscopically injected to reduce LES pressure, but relief usually lasts only 6 months and may affect future surgical intervention. Dilation with pneumatic balloon produces a controlled disruption of the LES fibers. Although there is a high risk of esophageal perforation, pneumatic dilation leads to longer symptomatic improvement. If needed, surgical myotomy to disrupt the LES fibers with or without anti-reflux procedure is the procedure of choice.

Our patient underwent esophageal manometry, which was consistent with type II achalasia. He had an upper endoscopy with pneumatic balloon dilation. Initially, his dysphagia resolved. At the 2-week follow-up, his symptoms began to reappear and he underwent repeat pneumatic dilation with a larger diameter balloon. He has been asymptomatic for the past year. GI continues to follow him as symptoms can recur years after dilation.

References and Suggested Readings

Kahrilas P, Bredenoord A, Fox M, et al. The Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(2):160-174.

Moonen A, Boeckxstaens G. Current diagnosis and management of achalasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(6):484-490.

To refer a patient to the Suzi and Scott Lustgarten Center for GI Motility, call 215-590-1678 or email motilitycenter@email.chop.edu.