A 6-week-old male (BS) was in the operating room at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for a routine hernia repair. The anesthesiologist was attempting to secure an airway for surgery via endotracheal tube (ETT) intubation. Immediately, he knew something was not right; the endotracheal tube would not pass into the child’s airway. The anesthesiologist paged an Airway surgeon to his operating room. Luv Javia, MD, arrived and the airway team quickly mobilized to perform a microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy (MLB), to assess the airway.

The MLB determined the child had complete tracheal rings starting right from the inferior most aspect of the larynx and going all the way down to the distal most aspect of the trachea (Figure 1). With this new knowledge, Dr. Javia adeptly and safely intubated the child using the smallest ETT, a 2.5, and the general surgery team was able to proceed with hernia operation. Following extubation at the end of the surgery, the infant moved to the Newborn/Infant Intensive Care Unit (N/IICU) for airway observation to monitor for airway swelling or respiratory compromise, which may result from manipulation of a significantly narrow trachea.

After surgery, Dr. Javia reviewed the images and findings from the MLB with the family. Upon discussing his history, details arose. The child required supplemental airway assistance after birth and a short NICU stay for respiratory support. Since being home, he struggled with weight gain and had intermittent inspiratory stridor at times associated with retractions. His mother also reported “heavy breathing” at times. Combining the operating room findings and the patient’s history, Dr. Javia recommended further studies to delineate his unique anatomy and to remain in the NICU for airway observation.

Additional diagnostic testing

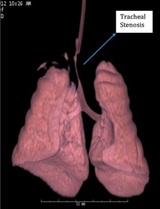

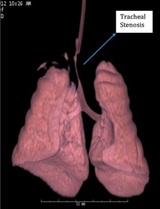

One of the studies recommended was a CT Angiography (CTA) of the chest with 3D reconstruction. This test revealed an entire stenotic trachea, from the larynx to carina, with complete tracheal rings. The trachea was 2 mm at its narrowest. Another surprise from the CTA was the discovery that BS also had anomalous cardiac vasculature: a left pulmonary artery sling (LPA sling). With LPA slings, the left pulmonary artery originates off the right pulmonary artery instead of from the main pulmonary artery branch. This results in the left pulmonary artery wrapping around the trachea and further narrowing the distal trachea. Due to the additional cardiovascular findings, Dr. Javia consulted with the cardiothoracic (CT) surgery team. Stephanie Fuller, MD, one of CHOP’s CT surgeons who collaborates with the Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders with infants and children who have complete tracheal rings, provided her expertise. After further discussion and review of all of the studies (MLB, CTA Chest), it was decided the safest approach would be a joint procedure with CT surgery to reconstruct BS’s narrowed trachea as well as address the LPA sling at the same time.

Surgery Day

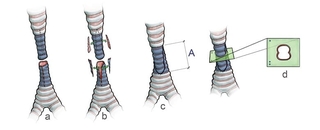

The surgical plan was a median sternotomy, cardiopulmonary bypass, correction of the LPA sling, and then a slide tracheoplasty (Figure 2).

Repair of the LPA sling is performed at the same time for a number of reasons. It reduces the pressure the sling exerts wrapped around the trachea, (now a repaired trachea). Additionally, since the child needs to have a median sternotomy (chest incision) in order to repair the tracheal stenosis, it makes sense to concurrently address the vascular anomaly under the general anesthesia.

The child recovered in the NICU. Postoperative care focuses on pain management, sternotomy precautions, dressing management to the sternum, and keeping the head midline and flexed. Keeping the head midline and flexed reduces hyperextension, which can cause tension on the suture line. Speech and language pathologists perform feeding evaluations and therapy to safely increase oral intake.

Physical therapist and occupational therapists help transition the child out of bed and back to normal daily life activities. He was successfully extubated on post-operative day 2. He required a few days of supplemental oxygen due to

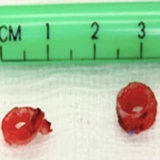

fluid overload but quickly weaned to room air. His breathing vastly improved; he no longer had noisy breathing or retractions. A repeat MLB performed about a week after extubation and then a week after that during his cardiac stent placement was done to ensure airway patency (Figures 3 & 4). The family was educated on what endotracheal tube to use and to advocate for a shallow intubation if the child needed future intubations, as the trachea is now shorter but wide in diameter.

Tracheal stenosis discussion

Complete tracheal rings and long segment tracheal stenosis

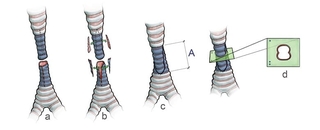

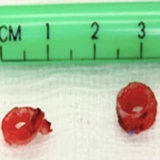

Complete tracheal rings are a very rare birth defect where the cartilage forms complete “O” rings instead of the usual “C” shaped rings (Figure 5). These complete rings narrow the airway and often involve more than 50% of the tracheal airway and can even involve the entire trachea as in this case study. Although this disorder is very rare, it can often result in as high as 80% mortality if not brought to the attention of specialized care. Children with this disorder often have associated conditions with cardiovascular anomalies (such as a ventricular septal defect, Tetralogy of Fallot, and a LPA sling), lung anomalies, or genetic syndromes.

When to refer

Signs and symptoms

Infants and children with complete tracheal rings and long segmented tracheal stenosis can have wet, inspiratory stridor (a high pitched type of noisy breathing); poor weight gain; retractions during breathing; chest congestion, and difficult intubation history. Other children have presented with frequent pneumonias, cyanotic episodes (blue spells), or inability to wean from an ETT and mechanical ventilation. The chest congestion, frequent pneumonias and upper respiratory infections result from ineffective airway clearance due to the stenosis. Some infants and children have mild symptoms of tracheal stenosis and may not know until they have an elective surgery that requires intubation. In other cases, the child is in such distress when they are born that they require immediate evaluation in the operating room.

Questions to consider in obtaining the history if suspicious of complete tracheal rings and long segmented tracheal stenosis are:

- Do you hear stridor or noisy breathing?

- When they breathe, do they sound like a dishwasher with wet, noisy breathing?

- If they have been intubated, was there any report of the team having difficulty placing the breathing tube?

- Have they had any frequent pneumonias, upper respiratory infections, or chest congestion?

- Is there any history of tracheomalacia?

- have they had any cardiac, pulmonary, or genetic anomalies?

- Have they had any cyanosis or dusky quality to the child with crying or agitation?

Work up for complete tracheal rings and long segmented tracheal stenosis

The diagnostic work up is both MLB and a CTA. The MLB provides a visual of the airway disorder while the CT angiogram with 3D reconstruction demonstrates the extent and if there are any concurrent cardiac anomalies (Figure 6). Genetics may be involved due to the association of complete tracheal rings and long segmented tracheal stenosis with some syndromes. A pulmonary consult or office visit may be involved to determine ways to optimize airway clearance prior to surgery and after surgery.

Treatment

For children with mild symptoms, they are monitored on an outpatient basis, with office visits and annual MLBs to assess the stenosis. Their trachea remains open enough in diameter for participating in activities without impeding airway clearance.

Slide tracheoplasty is the gold standard treatment for children with long segment tracheal stenosis who are significantly symptomatic, suffering from frequent prolonged respiratory illnesses, or whose daily activities are affected. Previous surgical methods to manage these children were inadequate. Patch tracheoplasty involved using a pericardial patch to augment the airway, but still resulted in high rates of life threatening tracheomalacia. Tracheal resection was often inadequate or not possible due to the length of the stenosis that needs to be removed and the resulting tracheal ends that may not be able to reapproximate easily. Finally, rib cartilage tracheoplasty involved using rib cartilage to augment the narrowed airway but unfortunately relied on harvesting a sizeable graft from the rib cage. This is not usually possible in young children/infants. Slide tracheoplasty is typically superior to these antiquated surgical management options, with greatly decreased mortality rates, shorter hospitalizations and quicker recovery. Advantages include the ability to reconstruct with normal, vascularized, tracheal tissue; less tension on the anastomosis site; less granulation tissue development in the trachea at the surgical site and continued tracheal growth over time.

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

A 6-week-old male (BS) was in the operating room at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for a routine hernia repair. The anesthesiologist was attempting to secure an airway for surgery via endotracheal tube (ETT) intubation. Immediately, he knew something was not right; the endotracheal tube would not pass into the child’s airway. The anesthesiologist paged an Airway surgeon to his operating room. Luv Javia, MD, arrived and the airway team quickly mobilized to perform a microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy (MLB), to assess the airway.

The MLB determined the child had complete tracheal rings starting right from the inferior most aspect of the larynx and going all the way down to the distal most aspect of the trachea (Figure 1). With this new knowledge, Dr. Javia adeptly and safely intubated the child using the smallest ETT, a 2.5, and the general surgery team was able to proceed with hernia operation. Following extubation at the end of the surgery, the infant moved to the Newborn/Infant Intensive Care Unit (N/IICU) for airway observation to monitor for airway swelling or respiratory compromise, which may result from manipulation of a significantly narrow trachea.

After surgery, Dr. Javia reviewed the images and findings from the MLB with the family. Upon discussing his history, details arose. The child required supplemental airway assistance after birth and a short NICU stay for respiratory support. Since being home, he struggled with weight gain and had intermittent inspiratory stridor at times associated with retractions. His mother also reported “heavy breathing” at times. Combining the operating room findings and the patient’s history, Dr. Javia recommended further studies to delineate his unique anatomy and to remain in the NICU for airway observation.

Additional diagnostic testing

One of the studies recommended was a CT Angiography (CTA) of the chest with 3D reconstruction. This test revealed an entire stenotic trachea, from the larynx to carina, with complete tracheal rings. The trachea was 2 mm at its narrowest. Another surprise from the CTA was the discovery that BS also had anomalous cardiac vasculature: a left pulmonary artery sling (LPA sling). With LPA slings, the left pulmonary artery originates off the right pulmonary artery instead of from the main pulmonary artery branch. This results in the left pulmonary artery wrapping around the trachea and further narrowing the distal trachea. Due to the additional cardiovascular findings, Dr. Javia consulted with the cardiothoracic (CT) surgery team. Stephanie Fuller, MD, one of CHOP’s CT surgeons who collaborates with the Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders with infants and children who have complete tracheal rings, provided her expertise. After further discussion and review of all of the studies (MLB, CTA Chest), it was decided the safest approach would be a joint procedure with CT surgery to reconstruct BS’s narrowed trachea as well as address the LPA sling at the same time.

Surgery Day

The surgical plan was a median sternotomy, cardiopulmonary bypass, correction of the LPA sling, and then a slide tracheoplasty (Figure 2).

Repair of the LPA sling is performed at the same time for a number of reasons. It reduces the pressure the sling exerts wrapped around the trachea, (now a repaired trachea). Additionally, since the child needs to have a median sternotomy (chest incision) in order to repair the tracheal stenosis, it makes sense to concurrently address the vascular anomaly under the general anesthesia.

The child recovered in the NICU. Postoperative care focuses on pain management, sternotomy precautions, dressing management to the sternum, and keeping the head midline and flexed. Keeping the head midline and flexed reduces hyperextension, which can cause tension on the suture line. Speech and language pathologists perform feeding evaluations and therapy to safely increase oral intake.

Physical therapist and occupational therapists help transition the child out of bed and back to normal daily life activities. He was successfully extubated on post-operative day 2. He required a few days of supplemental oxygen due to

fluid overload but quickly weaned to room air. His breathing vastly improved; he no longer had noisy breathing or retractions. A repeat MLB performed about a week after extubation and then a week after that during his cardiac stent placement was done to ensure airway patency (Figures 3 & 4). The family was educated on what endotracheal tube to use and to advocate for a shallow intubation if the child needed future intubations, as the trachea is now shorter but wide in diameter.

Tracheal stenosis discussion

Complete tracheal rings and long segment tracheal stenosis

Complete tracheal rings are a very rare birth defect where the cartilage forms complete “O” rings instead of the usual “C” shaped rings (Figure 5). These complete rings narrow the airway and often involve more than 50% of the tracheal airway and can even involve the entire trachea as in this case study. Although this disorder is very rare, it can often result in as high as 80% mortality if not brought to the attention of specialized care. Children with this disorder often have associated conditions with cardiovascular anomalies (such as a ventricular septal defect, Tetralogy of Fallot, and a LPA sling), lung anomalies, or genetic syndromes.

When to refer

Signs and symptoms

Infants and children with complete tracheal rings and long segmented tracheal stenosis can have wet, inspiratory stridor (a high pitched type of noisy breathing); poor weight gain; retractions during breathing; chest congestion, and difficult intubation history. Other children have presented with frequent pneumonias, cyanotic episodes (blue spells), or inability to wean from an ETT and mechanical ventilation. The chest congestion, frequent pneumonias and upper respiratory infections result from ineffective airway clearance due to the stenosis. Some infants and children have mild symptoms of tracheal stenosis and may not know until they have an elective surgery that requires intubation. In other cases, the child is in such distress when they are born that they require immediate evaluation in the operating room.

Questions to consider in obtaining the history if suspicious of complete tracheal rings and long segmented tracheal stenosis are:

- Do you hear stridor or noisy breathing?

- When they breathe, do they sound like a dishwasher with wet, noisy breathing?

- If they have been intubated, was there any report of the team having difficulty placing the breathing tube?

- Have they had any frequent pneumonias, upper respiratory infections, or chest congestion?

- Is there any history of tracheomalacia?

- have they had any cardiac, pulmonary, or genetic anomalies?

- Have they had any cyanosis or dusky quality to the child with crying or agitation?

Work up for complete tracheal rings and long segmented tracheal stenosis

The diagnostic work up is both MLB and a CTA. The MLB provides a visual of the airway disorder while the CT angiogram with 3D reconstruction demonstrates the extent and if there are any concurrent cardiac anomalies (Figure 6). Genetics may be involved due to the association of complete tracheal rings and long segmented tracheal stenosis with some syndromes. A pulmonary consult or office visit may be involved to determine ways to optimize airway clearance prior to surgery and after surgery.

Treatment

For children with mild symptoms, they are monitored on an outpatient basis, with office visits and annual MLBs to assess the stenosis. Their trachea remains open enough in diameter for participating in activities without impeding airway clearance.

Slide tracheoplasty is the gold standard treatment for children with long segment tracheal stenosis who are significantly symptomatic, suffering from frequent prolonged respiratory illnesses, or whose daily activities are affected. Previous surgical methods to manage these children were inadequate. Patch tracheoplasty involved using a pericardial patch to augment the airway, but still resulted in high rates of life threatening tracheomalacia. Tracheal resection was often inadequate or not possible due to the length of the stenosis that needs to be removed and the resulting tracheal ends that may not be able to reapproximate easily. Finally, rib cartilage tracheoplasty involved using rib cartilage to augment the narrowed airway but unfortunately relied on harvesting a sizeable graft from the rib cage. This is not usually possible in young children/infants. Slide tracheoplasty is typically superior to these antiquated surgical management options, with greatly decreased mortality rates, shorter hospitalizations and quicker recovery. Advantages include the ability to reconstruct with normal, vascularized, tracheal tissue; less tension on the anastomosis site; less granulation tissue development in the trachea at the surgical site and continued tracheal growth over time.

Recommended reading

Airway Disorders Center

Your child will receive advanced care and surgery from our experts in the Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders.

Contact us

Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders