A few years before Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia launched the Community Asthma Prevention Program (CAPP) in 1997, our colleagues in the Emergency Department sent weekly tallies of how many patients from CHOP’s original off-site primary care practice at 39th Street came to the ED for asthma-related problems.

It was a lot.

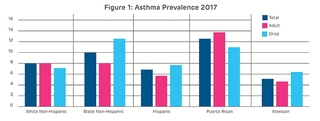

And it wasn’t surprising. The practice drew patients from West and Southwest Philadelphia, communities that were then, as now, predominantly Black and poor. First, we checked patients’ medical records to make sure we were following the treatment guidelines for these patients. We were. Then we turned to determining what barriers families experienced to consistent asthma control. The results fell into 2 categories: Not truly understanding how to effectively and consistently give asthma medications, and everything else connected to their complex, complicated lives. Now those nonmedical social determinants of health (SDOH)—such as housing, poverty, food insecurity, unsafe neighborhoods and the stress of living in those difficult conditions — account for as much of 80% of a child’s overall health, studies show.

The first step of the CAPP was to work on the education piece. We focused on short group sessions with parents and soon moved to peer educators: parents teaching other parents; high school students teaching kids. It helped but wasn’t enough. We needed to move to addressing the child’s environment.

Pioneering use of Community Health Workers for asthma control

CAPP began using community health workers, lay people with specific training, to go into the homes of patients who struggled to control their asthma and help families recognize and remove triggers. In addition to providing one-on-one in-home classes, our asthma home visitors brought items like mattress covers and roach bait with them, so families didn’t have to pay for them. At that time, in 1998, very few institutions were doing this—none in Pennsylvania—and most thought we were weird. But the results proved the personalized attention improved control. Children in CAPP had 30% to 40% fewer ED visits and 40% to 50% fewer hospitalizations.

CAPP’s asthma home visitors consistently reported other issues interfering with the children’s health: utilities shut off, lack of healthy food, deteriorating home conditions. Using the phone book—there wasn’t Google back then—we relied on a network community partners to help these families.

We also recognized that to get a handle on the asthma epidemic, we needed a collaborative, all-hands-on-deck approach that included researchers, public health professionals, educators/daycare staff, and parents in addition to healthcare professionals. We started an Annual Fighting Asthma Disparities Summit to share best practices and to support anyone who works to improve asthma outcomes; Oct. 5, 2021, will mark the 13th summit. CAPP also does extensive education of school personnel like teachers and coaches in addition to school nurses with the goal of keeping kids in the classroom and learning.

As an institution, CHOP was also doubling down on improving asthma outcomes. Parents and caregivers of hospitalized patients were given thorough education before their child could be discharged. After a pilot study proved its effectiveness, primary care pediatricians in the CHOP Care Network were automatically prompted by the electronic medical record to update and reinforce a child’s asthma care plan at each visit.

How to fix unhealthy homes?

We were making progress, but the issue of unhealthy homes for some of our children who were frequently hospitalized kept coming up.

Enter CAPP+, a joint program of CAPP and a new (in 2019) CHOP community outreach initiative, Healthier Together. Healthier Together is a 5-year, $25 million program created to move the needle on the social determinants of health (housing, food insecurity, poverty, and trauma) in 3 West Philadelphia ZIP codes close to CHOP’s Philadelphia campus.

Homes of families identified by asthma home visitors that are in need of repair to reduce asthma triggers can qualify for free improvements under CAPP+. The most frequent repairs involve removing the source of water intrusion (leaky roofs, plumbing, basements) and the resulting mold, and eliminating the source of pests (rodents and bugs). CAPP+ uses minority- and women-owned businesses from the neighborhood as contractors to infuse money into the area.

In its first 2 years of operation, CAPP+ repaired 67 homes. For the children with asthma living in those homes, it has meant fewer days with asthma symptoms and fewer hospital and emergency room visits. On May 25, CAPP+ was recognized by Environmental Protection Agency Mid-Atlantic Region’s Asthma Program as the inaugural recipient of its Asthma Community Champion award.

Progress, but more work to do

We feel encouraged that we’re making a difference for the children whose families participate in CAPP and CAPP+, but we’re limited.

As a healthcare institution, we need to take a wider view. CHOP has launched the Center for Health Equity to address, head-on, the challenges of healthcare disparities with bold strategies that lean on our strengths as an institution built on making breakthroughs with our partners. I’m excited to have been appointed the Senior Director of the center, where I will closely partner with teams in CHOP’s Center for Healthcare Quality and Analytics and Healthier Together to continuously improve the health and healthcare of CHOP’s patients and those in the surrounding Philadelphia community.

Reference and further reading

Bryant-Stephens T, Kurian C, Guo R, Zhao H. Impact of a household environmental intervention delivered by lay health workers on asthma symptom control in urban, disadvantaged children with asthma. AJPH. 2009;99(S3):S657-S665.

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

A few years before Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia launched the Community Asthma Prevention Program (CAPP) in 1997, our colleagues in the Emergency Department sent weekly tallies of how many patients from CHOP’s original off-site primary care practice at 39th Street came to the ED for asthma-related problems.

It was a lot.

And it wasn’t surprising. The practice drew patients from West and Southwest Philadelphia, communities that were then, as now, predominantly Black and poor. First, we checked patients’ medical records to make sure we were following the treatment guidelines for these patients. We were. Then we turned to determining what barriers families experienced to consistent asthma control. The results fell into 2 categories: Not truly understanding how to effectively and consistently give asthma medications, and everything else connected to their complex, complicated lives. Now those nonmedical social determinants of health (SDOH)—such as housing, poverty, food insecurity, unsafe neighborhoods and the stress of living in those difficult conditions — account for as much of 80% of a child’s overall health, studies show.

The first step of the CAPP was to work on the education piece. We focused on short group sessions with parents and soon moved to peer educators: parents teaching other parents; high school students teaching kids. It helped but wasn’t enough. We needed to move to addressing the child’s environment.

Pioneering use of Community Health Workers for asthma control

CAPP began using community health workers, lay people with specific training, to go into the homes of patients who struggled to control their asthma and help families recognize and remove triggers. In addition to providing one-on-one in-home classes, our asthma home visitors brought items like mattress covers and roach bait with them, so families didn’t have to pay for them. At that time, in 1998, very few institutions were doing this—none in Pennsylvania—and most thought we were weird. But the results proved the personalized attention improved control. Children in CAPP had 30% to 40% fewer ED visits and 40% to 50% fewer hospitalizations.

CAPP’s asthma home visitors consistently reported other issues interfering with the children’s health: utilities shut off, lack of healthy food, deteriorating home conditions. Using the phone book—there wasn’t Google back then—we relied on a network community partners to help these families.

We also recognized that to get a handle on the asthma epidemic, we needed a collaborative, all-hands-on-deck approach that included researchers, public health professionals, educators/daycare staff, and parents in addition to healthcare professionals. We started an Annual Fighting Asthma Disparities Summit to share best practices and to support anyone who works to improve asthma outcomes; Oct. 5, 2021, will mark the 13th summit. CAPP also does extensive education of school personnel like teachers and coaches in addition to school nurses with the goal of keeping kids in the classroom and learning.

As an institution, CHOP was also doubling down on improving asthma outcomes. Parents and caregivers of hospitalized patients were given thorough education before their child could be discharged. After a pilot study proved its effectiveness, primary care pediatricians in the CHOP Care Network were automatically prompted by the electronic medical record to update and reinforce a child’s asthma care plan at each visit.

How to fix unhealthy homes?

We were making progress, but the issue of unhealthy homes for some of our children who were frequently hospitalized kept coming up.

Enter CAPP+, a joint program of CAPP and a new (in 2019) CHOP community outreach initiative, Healthier Together. Healthier Together is a 5-year, $25 million program created to move the needle on the social determinants of health (housing, food insecurity, poverty, and trauma) in 3 West Philadelphia ZIP codes close to CHOP’s Philadelphia campus.

Homes of families identified by asthma home visitors that are in need of repair to reduce asthma triggers can qualify for free improvements under CAPP+. The most frequent repairs involve removing the source of water intrusion (leaky roofs, plumbing, basements) and the resulting mold, and eliminating the source of pests (rodents and bugs). CAPP+ uses minority- and women-owned businesses from the neighborhood as contractors to infuse money into the area.

In its first 2 years of operation, CAPP+ repaired 67 homes. For the children with asthma living in those homes, it has meant fewer days with asthma symptoms and fewer hospital and emergency room visits. On May 25, CAPP+ was recognized by Environmental Protection Agency Mid-Atlantic Region’s Asthma Program as the inaugural recipient of its Asthma Community Champion award.

Progress, but more work to do

We feel encouraged that we’re making a difference for the children whose families participate in CAPP and CAPP+, but we’re limited.

As a healthcare institution, we need to take a wider view. CHOP has launched the Center for Health Equity to address, head-on, the challenges of healthcare disparities with bold strategies that lean on our strengths as an institution built on making breakthroughs with our partners. I’m excited to have been appointed the Senior Director of the center, where I will closely partner with teams in CHOP’s Center for Healthcare Quality and Analytics and Healthier Together to continuously improve the health and healthcare of CHOP’s patients and those in the surrounding Philadelphia community.

Reference and further reading

Bryant-Stephens T, Kurian C, Guo R, Zhao H. Impact of a household environmental intervention delivered by lay health workers on asthma symptom control in urban, disadvantaged children with asthma. AJPH. 2009;99(S3):S657-S665.

Contact us

Community Asthma Prevention Program (CAPP)